As historian Rainer Simons wrote, “The BMW 328 is legendary. It is acknowledged by car enthusiasts the world over as having a special pedigree, presence, and uniqueness. It is definitely among the most attractive, successful, and influential sports cars ever built.” The gorgeous 328 never debuted at some press event or auto show. It was unveiled on the track, Germany’s legendary Nürburgring—and handily won its first race right then and there. It then won Italy’s famed Mille Miglia, a race won only thrice by non-Italians, despite possessing 90 less horsepower than the Alfa that won the year before. The 328, then, set the precedent for lightweight, balanced engineering that has inspired Bimmers and much else ever since. We owe it much.

In 1934 the company had gathered together its vehicle development activities under the watchful eye of Fritz Fiedler in Eisenach. His team was only 20-strong in those early days, but the department soon began to grow. For example, on 1 October 1936 body specialist Wilhelm Kaiser arrived in Eisenach to strengthen the team. His tasks included drawing up body designs for the 328. Using the hand-built prototypes as a basis, he designed a shape which borrowed the smooth, flowing stylistic features of the new 326 and could be assembled with relatively simple tools from pre-pressed parts. All of which made the BMW 328 a harmonious blend of form and function.

Few cars can claim to hold as much fascination in the eyes of the public 75 years after their premiere as the BMW 328. Built between 1936 and 1940, the BMW 328 laid down a milestone in automotive history and was the most successful sports car on the pre-war (WWII) racing scene. Agility, acceleration, reliability and lightweight construction – the BMW designers focused on the essentials in the development of the 328, ushering in a new era in the process.

In the BMW 328, they developed a refined sports car whose qualities would provide one of the pillars for further developments over the following decades. Nowadays, the creation of a new car evolves as part of a process costing millions that is drawn out over several years. It includes the contributions of hundreds of engineers and designers working under the strictest secrecy in development center’s and design studios. By extreme contrast, the BMW 328 was put together in double-quick time with minimal use of materials and manpower. When Schleicher and Fiedler conceived the BMW 328, there was no such thing as market research, a design department or a wind tunnel at BMW, never mind the electronic tools their counterparts take for granted today. Back then, designers were to be found huddled around drawing boards or in the testing workshop, using their hands to lend form to their ideas.

The BMW 328 is a masterpiece of the engineering art, a credit to the level of achievement of the original designers. If you were to single out one aspect of what makes the BMW 328 so special, it would be the coherence of the overall concept. The sports car as a whole was not particularly revolutionary, yet its individual components – the drivetrain, body and chassis – came together to form a superior whole. Over 75 years later, it remains a convincing and impressively resolved package today.

When it came to getting into your seat, the BMW 328 first required you to reach inside the car, as the doors had no exterior handles. Once settled in behind the wheel, you were greeted by a pair of pleasantly clear dials – the rev counter on the left and a 180 km/h speedometer of equal diameter to its right. These were joined by three smaller instruments charged with keeping the driver informed of fuel levels, oil pressure and water temperature. Buttons and switches for the starter motor, lights, choke and direction indicators rounded off the dashboard. Standard fixtures and fittings also included a glove compartment with a lid, pockets in the doors and a well-equipped tool box. In the center of the black, three-spoke steering wheel was the button for the two Bosch horns positioned behind the double-kidney grille.

And in case of a dead battery, there was a hole for a manual crank in the radiator cover underneath the double-kidney grille – a standard feature at the time. The spare wheel was accommodated in a visible recess in the rear end. The first three prototypes had no doors, nor a spot for the spare wheel; their windscreen was low and single-piece in design. By contrast, the later series-produced cars had screens consisting of two halves – angled in a V – which could be folded down individually and had a wiper for each. In addition, the BMW 328 came standard with patented central-locking Kronprinz disc wheels with 5.25×16 tyres. Behind them, hydraulic brakes with 280 mm diameter drums gave good stopping distances for the time.

A particularly sporty touch was provided by the two leather belts strapped over the bonnet. Along with the classic “double-kidney” design of the radiator grille, these light-brown cowhide belts – held in place by a clip-lock – represented a prominent stylistic element of the BMW 328.

But it wasn’t only the hood straps that made a convincing impression; the BMW 328 also boasted road-holding that no other car at the time could match. The outstanding qualities of the BMW 328 were the fruits of a design principle introduced with the BMW 303: lightweight construction. Since the early 1930s BMW had been more synonymous with this concept than perhaps any other carmaker. Key elements of this innovative design principle include the use of materials with the lowest possible specific weight – where the construction of the car allows – and cutting-edge chassis and body construction techniques which represent a departure from conventional thinking.

The tubular frame construction developed by engineer Fritz Fiedler and patented by BMW played an important role in limiting the weight of the BMW 328 to 780 kilos. This frame consisted of two longitudinal tubes with circular cross sections which converged in an “A” shape from the rear wheels to the front of the car, accommodating the width of the engine, and were connected by rectangular profiles. The strong, lightweight frame supported the front suspension with lower wishbones and an upper transverse leaf spring, while the live rear axle had semi-elliptical longitudinal leaf springs.

The tube cross sections then tapered towards the areas at the rear subject to lower bending forces, helping to significantly reduce the weight of the frame. This special tube design also led to improved bending resistance and torsional rigidity – and therefore gave the car better and more direct handling. A chassis with a tubular frame therefore had huge advantages over constructions featuring the U-section frame more common at the time.

However, many motorists back in those days believed that a heavier car was safer and also easier to control than a lightweight model. You would hear the same opinion again and again; that only a heavy car would “stick to the road like glue”. However, BMW engineers pointed out that road-holding was directly linked to centrifugal force, which depended on mass – the greater the mass, the greater the centrifugal force. Added to such, stronger inertial forces also affect all other sprung and rotating parts of the car. A higher un-laden weight requires increased output to propel the dead weight, and high un-laden weight also places significantly greater loads on engine and suspension components. All of which means that lowering a car’s weight offers various benefits in driving dynamics.

Although the BMW 328 was developed on the basis of the BMW 319/1, it differed significantly in both its exterior appearance and under the skin. Indeed, the technical attributes of the new sports car combined to make the 319/1 “look rather old” when you compared them directly.

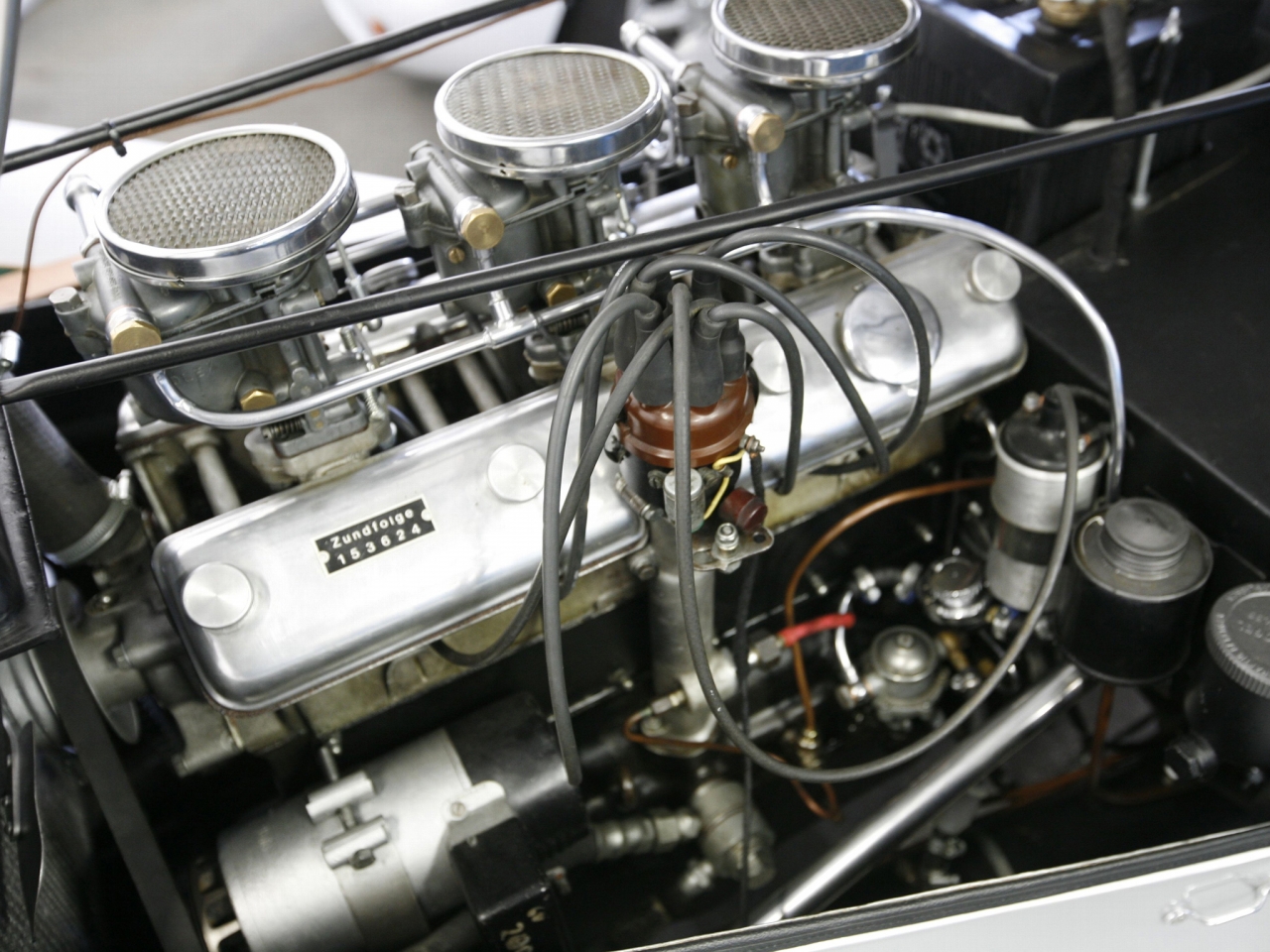

The lack of resources for an all-new design meant that the BMW 328 had to make do with a modified version of the 50 hp engine from the BMW 326. The 2-litre grey cast iron block was given a new cylinder head (made from an aluminium alloy) with valves arranged in a “V”. Valve control was the job of the side-mounted camshaft using bell cranks on the exhaust side and transverse pushrods. This impressively effective upgrade increased output to 80 hp at 4,500 revs per minute; about 30bhp more that of the 319/1 model sports car that used an engine with similar only slightly less displacement.

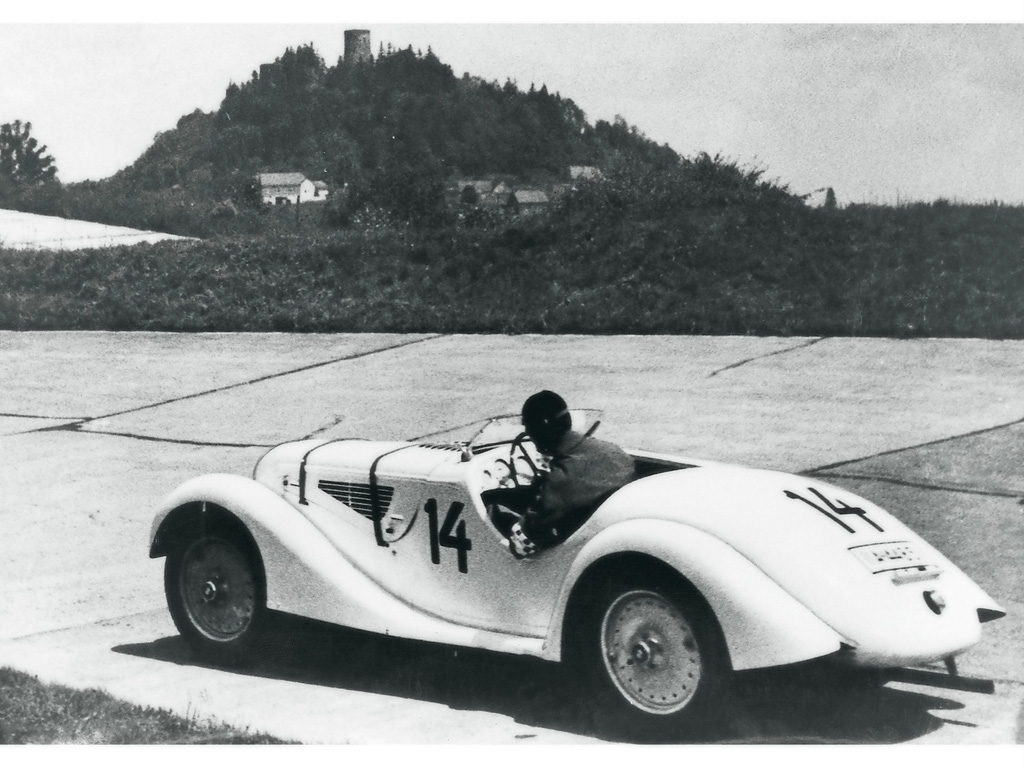

Saturday, 13 June 1936, the day before the premiere of the BMW 328; a busy day at the Nürburgring draws to a close, but the air is still heavy with anticipation. The weather forecast for the following day is less than promising, but Ernst Jakob Henne was relaxed: “We’re used to these conditions at the ‘Ring,” he shrugged. “A Sunday without rain is not a proper Eifel Sunday.”

Henne would be piloting the new car, the latest distinction of a career which had already seen him set a string of world records on BMW motorcycles over previous years. In practice, his car ran like clockwork, and the next day was expected to be much the same. The car’s engineers Rudolf Schleicher and Fritz Fiedle, meanwhile, were trying their best to disguise their nerves, but to little avail. Their anxiousness was justified; after all, scheduled for the following day was the debut of their sporty new two-seater – in one of the most important races of the year.

Sunday, 14 June 1936 – the day of the premiere, 34 runners were listed in the sports car category of the International Eifel Race. Seven of these were entered in the 2-litre class, and five were BMWs. Four were “Typ 319/1” cars, the other Ernst Jakob Henne’s snow-white Roadster. The car stood out from the crowd, its body boasting far more flowing forms, a curved front end with a pair of slim, kidney-shaped air intakes similar to those of the BMW 326 presented at the Berlin Motor Show that spring, headlights integrated into the front wings, a low, sloping windscreen and a bulbous rear end. Out of sight, yet most certainly not out of mind after the car’s lap times in practice, was the new engine lurking beneath the bonnet. The sound rumbling to the surface through the bonnet’s two leather securing belts indicated the presence of a six-cylinder unit producing maybe 80 or even 90 horsepower.

As forecast, the pleasant conditions of practice day were usurped by rain and mist on Sunday. But that didn’t deter 250,000 enthusiastic fans from flocking to the circuit to witness the most exciting race of the season.

Indeed, at a time when powerful supercharged “Kompressor” machines ruled the racing roost, the BMW 328 Roadster – weighing just 780 kilograms and developing a modest 80 horsepower in series production form – was a genuine sensation. And sure enough, the new Roadster wasted no time in putting its burly supercharged rivals firmly in their place in its debut outing at the Nürburgring on 14 June 1936.

The new BMW 328 promptly put its rivals – some of them with much higher-output engines – to the sword, breaking the Nürburgring lap record for sports cars in the process. “For undiluted, top-class racing the International Eifel Race at the Nürburgring was the place to be,” trumpeted the daily press. “One of the most impressive results of the day was the victory of world record-breaking motorcycle rider Ernst Jakob Henne in the non-supercharged sports car class up to two litres. He even managed to set the fastest lap time of any sports car!” reported one paper. “Henne squeezed incredible performance out of his new 2-litre car,” added a stunned ‘Die Motorwelt’. “What magnificent acceleration! … this sports car is quicker than all its supercharged rivals! Henne takes the victory by a clear margin.”

Henne’s dream race and the premiere of the BMW 328 have gone down in Nürburgring folklore. But that wasn’t the end of the story: the victory of the new sports car, internal designation “Baumuster 328”, marked the start of a legend which has secured BMW’s status as a synonym for sporting commitment to this day.

The maiden voyage win was to be followed by more than 200 others over a lifespan that lasted into the 1950s. It was a run of success unparalleled by any other model in its class; few other cars have left such an enduring impression on the company’s motor sport history as the BMW 328 with its 2.0-litre straight-six engine.

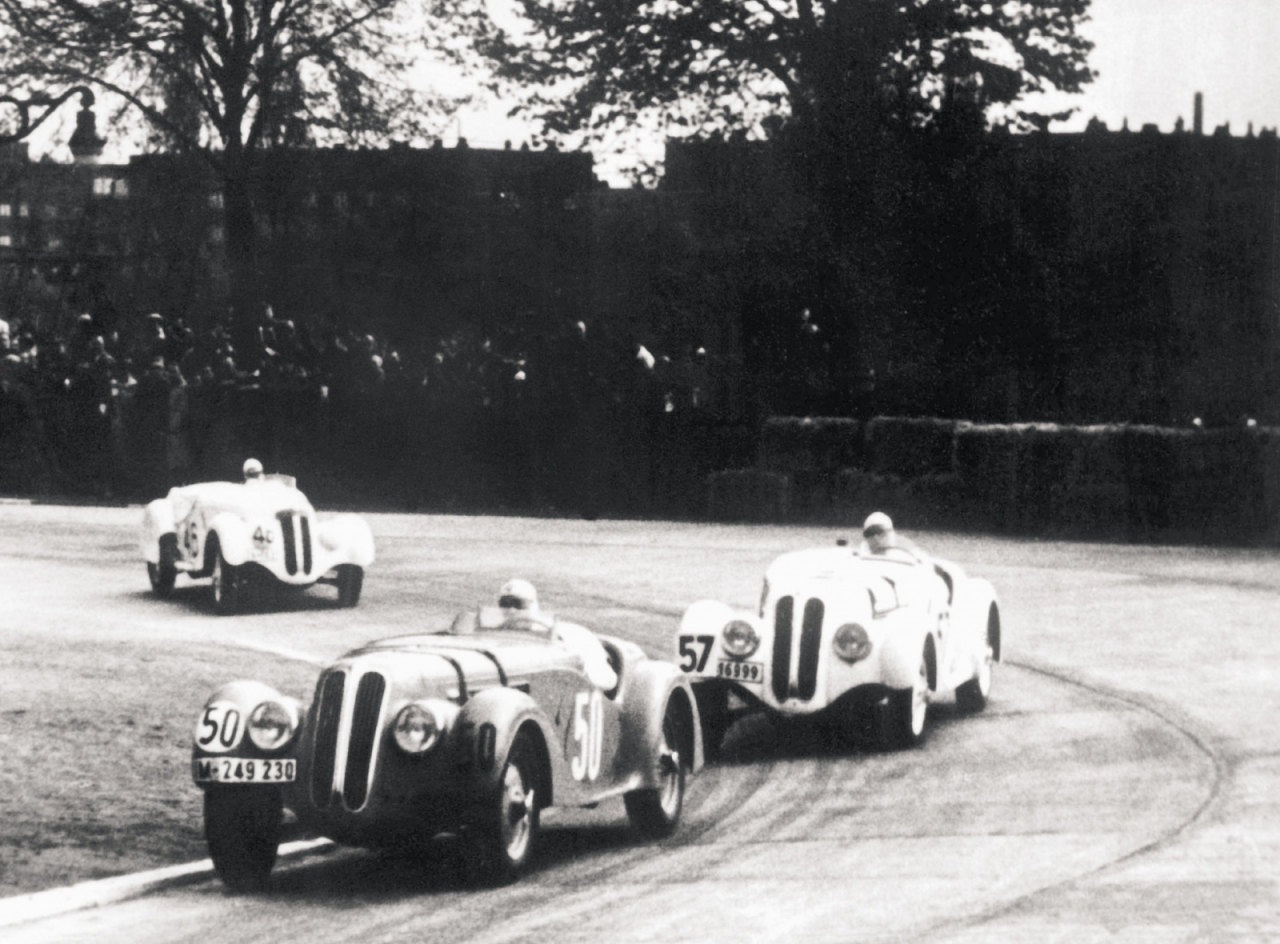

After the triumph at the Nürburgring, BMW set about conquering race tracks far and wide with a trio of BMW 328 prototypes. The universally positive reaction to the maiden victory of the new BMW sports car at the Nürburgring had sparked high expectations. There were some initial problems under sustained loads in the French Grand Prix at the high-speed Montlhéry circuit, but the flow of fastest laps and victories soon resumed. As early as August that year, British BMW importer H. J. Aldington swept to glory in the Schleißheimer Dreiecksrennen race at the wheel of a BMW 328. And it was Aldington who urged the BMW top brass to enter another race outside Germany. A triumvirate of prototypes in green Frazer-Nash-BMW livery lined up for the Tourist Trophy in Ireland – and promptly sealed a clean sweep of the top three places.

However, it was still the three pre-production cars taking it in turns to rack up the wins, with various different drivers at the wheel over the months following the premiere. Private customers were forced to play the waiting game, as production was slow to get into gear; the first cars were not delivered to customers until late April 1937. And so it was almost a full year after Henne’s dramatic debut before private BMW 328 owners could test out their new purchase in race action. Once the first customers did finally get their hands on their long awaited BMW 328, it was clear how the rest of the racing season would unfold. For example, at the 1937 Eifel Race there were nine BMW 328 racers on the grid, and the fight for victory would consequently be an in-house affair. Over the years that followed, only a handful of lackluster attempts were made by other cars to take on the hot-heeled BMWs.

Reports of victories continued to rain into Munich from every corner of Europe. And it wasn’t only class wins that the car was amassing so effortlessly, as much more powerfully-engined cars also succumbed to its irresistible will. The small 2-litre sports car was building a handsome collection of overall victories over once superior rivals. Sports car racing was fast being redefined, the BMW 328 giving the 2-litre class a powerful new contender.

On the road, its top speed of 155 km/h made it one of the quickest cars around. And, with only 464 examples ever made, the BMW 328 is today one of the most sought-after collector’s items on the market. Its allure lies in the timelessly beauty of an open-top two-seater, its still convincing engineering and the aura that countless racing victories had created around it. After all, the BMW 328 was not only one of the most visually appealing sports cars of the pre-war period, in the 1930s it was also the most successful racing machine in Europe.

The success of the BMW 328 lay in the sum of its parts: rigorously applied lightweight design, ideal weight distribution, aerodynamic lines, the perfect engine and a meticulously tuned chassis delivering flawless roadholding. All of which allowed it to underpin a fresh understanding of what a car could be, one which saw the engine’s output teaming up with the optimum interplay of all the car’s component parts – and complemented by maximum efficiency – to achieve success. These qualities enabled the BMW 328 to embody the values that still underpin the BMW brand today: dynamics, aesthetic appeal and a high degree of innovation.

The engineering below the surface of the BMW 328 was impressive indeed, but the car’s looks were also among its strengths. Indeed, viewed through 21st century eyes, this remains one of the most handsome sports cars of the 1930s. Its arresting looks certainly didn’t come about by chance; since the 30s BMW has paid very close attention to the aesthetic ingredients of vehicle development as well as to technical aspects.

The BMW 328 acted as a catalyst for change. Having made its debut as a racing car in 1936, series production of the BMW 328 finally began a year later. Far from being designed purely for racing, this was a “powerful everyday car for travel and sport”, as the advertising put it. However, there was none of the promotional fuss and press attention we would expect today for a sports car designed for road and touring use.

In spring 1938 Bayerische Motoren Werke delivered the 200th BMW 328 to its owner. And yet only 464 examples were produced up to 1940, leaving the 328 as a sought-after rarity in classic car circles today. It soon became clear that the team lacked the manpower to deal with future tasks, prompting the establishment on 1 September 1938 of the new “Künstlerische Gestaltung” design department, headed by Fritz Fiedler. This gave Munich a state-of-the-art design studio, where the designers worked with Plasticine models, taking a leaf out of their American counterparts’ book. This was where their ideas literally took shape, their designs – as today – translated into life-size models and then refined to create an emotional work of art. Over the following two and a half years, the design team was responsible for the conception of all cars in the planning stages and under development – the 330, 335, 332, Mille Miglia Roadster and Kamm Racing Saloon being notable examples.

Stay tuned for Part II which will go more in depth with these unique 328 variants…

Latest posts by Tom Schultz test #2 (see all)

- 2024 Durango Event - 24 February, 2024

- Drive 4 Corners 2022 Low-Key Event Concluded - 1 September, 2022

- Drive 4 Corners 2022 Informal Event Planned! - 6 June, 2022