BMW & USA Olympic Bobsled Documentary – Driving On Ice from Pat R Notaro III on Vimeo.

The 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, Russia, presented another unique opportunity for athletes from around the world to compete. Athletes prepare for years, and some even decades in order to compete and represent their respective countries. From ski-athalon to Super G; figure-skating to curling, and ice-hockey to bobsledding, there is something for everybody to enjoy. Now at the close of the Olympics, the US was once again among the leaders in total Olympic medal counts.

A surprising contributor to that value is the Team USA 2-person bobsled teams. Using of athletes of the past summer Olympic medalists, the USA women’s teams meant business by selecting Lolo Jones and Lauryn Williams as two brakemen of three sleds.

All Williams has done as a rookie is help the U.S. win three medals in her four World Cup races. “I joined bobsled just to be a helper and to add positive energy to the team,” Williams said. “If my name wasn’t called, I wasn’t going to be upset. I’ve enjoyed this journey. I’ve enjoyed getting to know everyone. I’ve enjoyed the challenge.”

About two hours after the team selection was made, Jones posted her reaction on Facebook, summing up the emotions of having another chance to compete for an Olympic medal. “Had I not hit a hurdle in Beijing I would not have tried to go to London to redeem myself,” she wrote. “Had I not got fourth in London I would not have tried to find another way to accomplish the dream. Bobsled was my fresh start. Bobsled humbled me. Bobsled made me stronger. Bobsled made me hungry. Bobsled made me rely on faith. Bobsled gave me hope. I push a bobsled but bobsled pushed me to never give up on my dreams.”

The women’s athletic abilities from the summer games events allowed for consistent launches atop the hill, quicker than almost all other teams. But of course, a good start is only as good as the success of the driver over the remaining distance of the course.

Where am I going with this and how is this whatsoever BMW related?

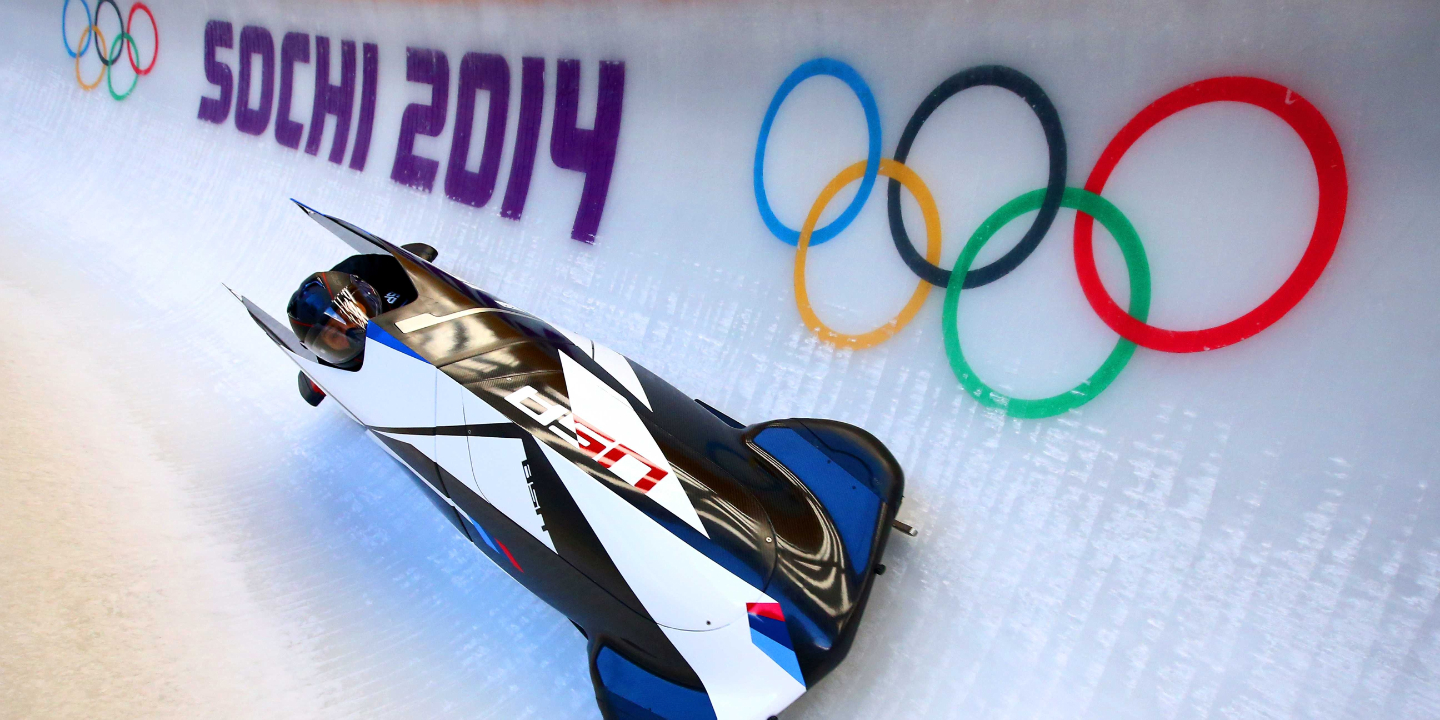

Well, a unique opportunity presented itself for the 2 man bobsled teams of Team USA. BMW North America was interested in teaming up with the USA bobsledders and working towards a faster, better sled. The design team worked vigorously to bring the best possible sled to Sochi; and in short time, only just two years.

Beating the world’s best is difficult even under ideal circumstances, but especially so when the odds are stacked against you. For years, American sledders have operated as one of the only prominent teams in the bobsled without receiving funding by the government. Interestingly, many of the big manufacturers in Europe use funding from their respective governments to help produce better sleds, and achieve success in the international stage set by the Olympics. Proof of this is in fact that the United States hasn’t won gold in the two-man bobseld since the 1936 Winter Games at Garmesh-Partenkirchen, Germany. Of course, back then the sport was only limited to men.

In a sport where hundredths of a second count, the U.S. switched from the Bo-Dyne designed chassis that former NASCAR race car driver Geoff Bodine and Chassis Dynamics developed for the U.S. heading into the 1994 Lillehammer Winter Olympics, to a new BMW design, which is manufactured at BMW Designworks in California.

While the Bo-Dyne sleds were a big leap for the U.S. back in 1994, Laubenstein; ex-Penske Racing employee, says the new BMW design puts the U.S. on a par with sleds used by the European teams that are designed with the aid of Ferrari.

Digital Trends was able to help explain how they did it. See original HERE.

This year, things are different. Hoping to build, then drive, a better sled, Team USA turned to the North American division of BMW, a company well-versed in speed, to help them in any way possible. The sled is like a third member of the team, and any weakness relative to the competition shows in the standings. So lead designer, Michael Scully (BMW Group DesignworksUSA Creative Director), started from scratch, at the most basic place: shape. “We didn’t want only to do a typical bobsled,” he says, “but we also wanted to understand why they were shaped the way they were for many, many years.”

Scully’s team created five distinct “families” of shapes – each color coded to match one of the Olympic rings – to understand what the basic architecture of the sled ought to be. This became the basis for their Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) testing. Essentially like sticking the designs in a computerized wind tunnel, the process helped narrow down five families to one. The big winner had the downforce sought after in race vehicles, helping lend a feeling of stability and control – no “floatiness” for the driver to fight – and more importantly showed the best reduction in drag.

Violent, noisy, and chaotic, it’s like steering a marble through a trip in the clothes dryer.

The BMW sleds have a redesigned cowling, or shape, with the body work done primarily through computational fluid dynamics, or CFD, which uses the aid of computers and mathematic algorithms to improve the efficiency of airflow around a part.

From there, the shape went through 69 different iterations, each sent out for CFD testing, making adjustment after adjustment trying to get the best results, all the while balancing the sport’s very specific, very prescriptive (and thereby restrictive) guidelines for sled construction. Rules govern everything from the sled’s weight and height, widths at different points up and down the body, the size of the bumpers to their position to the axels, the runners, how they’re attached, and enough other things to make for a hefty rulebook. Still, the sleds themselves, compared to something like a race car, are comparatively low-fi machines.

“There’s very few moving parts,” says Steven Holcomb, a three-time Olympian in Sochi and America’s top bobsled driver. “There’s no engine. There’s no power steering. There’s no anti-lock brakes. There’s no computer inside. There’s a lot that goes into these sleds, but at the same time, they’re so simple.” Whether by that relative simplicity or the giant stack of rules, when so much is taken out of a designer’s hands, the few areas left to make decisions become that much more significant. “Those are where the subtlety has to happen. It’s a sport of tiny subtleties hopefully adding up into something on a stopwatch,” Scully says.

The design BMW arrived at was smaller, with a lower center of gravity. Built with an autoclave-cured carbon-fiber body, it was also lighter, to the point weight had to be added to bring the thing up to code. Where, Scully won’t say (the first rule of Bobsled Design Secrets is do not talk about Bobsled Design Secrets). But shaving weight from the shell allowed Scully and his team to decide where those pounds – in the form of lead plates – should go back into the sled. This, he says, is a big advancement, affording better control of its behavior during a run. Still, lab-based testing could only accomplish so much.

“Computational fluid dynamics, they give you one set of answers or values, but it’s not necessarily the truth,” Scully says. “The only way you get the truth of the shape is when you get it on the track. That’s probably the most challenging aspect of this project, is that bobsleds experience such a huge variety of positions as they go down a track that their orientation to airflow and the track itself is constantly changing. That level of variability is something we had to design for as well. CFD values are one thing, but really you have to get it on to the track and understand what the pace is.”

The sled was also tested in the wind tunnel, however, chief designer Michael Scully even got on board for some test runs with U.S. bobsledders to make further improvements.

That pace, just as a reminder, is very, very fast: up near 90 miles an hour. As Scully himself learned when he took a ride in the four-man version of the bobsled. “That was their handshake,” he says. “Get in. “There’s no engine. There’s no power steering. There’s no anti-lock brakes. There’s no computer inside.”

Were he testing a race car, given his background, Scully could have hopped in the driver’s seat and done it himself, lap after lap. Bobsleds? Not so much. First, it’s a highly seasonal sport, with a limited number of venues. And when teams do get on the track, it might just be for two or three runs, rarely occurring under similar track conditions. Thanks to changes in weather, the track’s surface as multiple sleds chew it up, and other environmental factors. To make the process even more complicated, the world isn’t exactly littered with people who know how to pilot one of those things.

“It’s a unique skill that not a lot of other people have and you can’t take 500 laps and get used to it. You don’t have time to practice,” Holcomb says. “If we change something, we have one or maybe two runs. We’re going full speed the very first time we try to make a change. It’s very fast, very quick.” As a result, Scully became extremely dependent on Holcomb and his teammates for feedback, creating a unique marriage of designer and driver.

Certain fears were alleviated quickly. Given the smaller dimensions of the BMW sled, Scully worried its substantial passengers (Holcomb is 5-foot-8-inches, 231 lbs, his brakeman Steve Langton is 6-foot-3-inches, 227, and their teammates are similarly sized) wouldn’t fit inside the thing while it was stationary, let alone be able to leap in after pushing it at the start of a run. They did, and could. (Exhale.) On the other hand, early editions of the steering mechanisms left something to be desired, Holcomb says. There wasn’t nearly enough feel.

Some design concepts fell by the wayside, waylaid by the realities of the track. For example, one design including a pair of “fins” extending off the back of the sled tested very well in the lab. But once the sled was on the track, they started vibrating and chattering. Plus, it turned out the techs couldn’t do maintenance between runs with them attached, because they made it tough to roll the sled over by hand. “It was one of those learning experiences along the way,” Scully said. “In simulation, this is better. In reality, as soon as it starts flapping like that? No, it’s not better. And if the guys can’t use it the way they normally would and flip it over all the time, no, it’s not better.”

Throughout the process, Scully was in awe of Holcomb’s ability to maximize the value of every run, and what could be learned from it. “I call him a metronome. He can do exactly the same start time, every run. He can hit the same number — it didn’t have to be the fastest number, as long as it’s consistent.” From there, Holcomb’s expertise as a driver allowed him to detect incredible subtleties in the sled’s ride and steering despite the incredible violence of a bobsled run. “I have 10, 11 years of driving experience. I’m able to manipulate the sled and maneuver it in ways that a lot of other drivers can’t,” Holcomb says. And thanks to Scully’s racing background, relating what he felt on the track wasn’t complicated.

“I tell him some of the sensations I’m feeling and he’s able to relate to his driving experience and can understand that. I think it’s been a pretty good partnership,” Holcomb says. “The subtlety of input that the pilots are able to perceive would blow your mind,” Scully says. “There were times they’d ask for a small adjustment, and it would be like a little rubber band almost. Just a small tensioning device on a steering, and it’s like “Really, you can feel that?” and they would go down, come back, and have a direct reaction to what you had just implemented.”

The world of bobsledding is one in which secrets are tightly protected and new technology is greeted with great interest, as was the case when the US busted out its new toy at a World Cup race in Igls, Austria last January. “It blew everybody’s mind. Everybody’s kind of panicked,” Holcomb says. “(Then) I take it down the first run, and of course, I made a mistake going into the first curve and we ended up finishing 14th. There was kind of a sigh of relief around the world because we were so slow.”

They might be hyperventilating, now. Since that inauspicious debut, Holcomb and his teammates have made great strides in the BMW sled. Holcomb has won five two-man bobsled competitions this season, including a triumphant return to Igls in January. He’s considered among the favorites to take gold in Sochi.

If Holcomb is able to end America’s drought in two-man competition, it will represent not just a triumph of engineering and practical know-how, but of the power of collaboration: Two very different minds working together to shave hundredths and thousandths of seconds from a run, the difference between winning and losing.

“There’s three elements,” Holcomb says of winning a bobsled race. “You have to have a great push, a great driver, and you have to have a great sled. If you’re missing one of those at this level, you’re not gonna win. You’re not gonna be successful.”

The first two are up to the athletes. But in Sochi, there is every reason to believe the third is well taken care of.

“I happen to think these are going to be very good,” Darrin Steele, CEO of the U.S. bobsledding foundation, told the Associated Press. “Races are won by hundredths of a second. It’s maddening to think after all this we’ve maybe improved only a tenth of a second. But a tenth of a second over four runs is pretty significant.”

So what happened in Soichi?

Well if you weren’t paying attention to the bobsled results, let me fill you in. Darrin Steele, was correct in his thoughts. The 2-man bobsled teams had great success down the icy track. USA men were able to conquer the hill by earning a bronze medal, with none other than Steve Holcomb. They were edged out by the hometown favorite, Alexander Zubkov, who knew the track better than any other driver going down the hill, and took gold in both 2-man and 4-man bobsled. But still, Holcomb and the BMW sled earned the first medal for Team USA 2-man bobsledding in 62 years.

Team USA’s women claimed two of three possible Olympic medals by earning the Silver and Bronze with the new BMW-desgned sled. The American duo of Elana Meyers and Lauryn Williams in USA-1 was edged out by the Canadians by a mere 0.10 seconds. Humphries and Moyse, of Canada, finished a full second ahead of Jamie Greubel and Aja Evans in USA-2, the bronze winners. For Team USA, it was a major achievement to stand atop the podium. Williams used her athletic background to launch the women’s sleds from the starting gate to the podium, of course with the help of the new BMW sled, and the driving of Elana Meyers.

In this regard, the BMW sled achieved great success. It is a testament to the efforts of BMW North America and their work towards building The Ultimate Sledding Machine. Now the only questions that remains is, when can we buy one??

See the full BMW Documentary “Driving On Ice”:

Latest posts by Tom Schultz test #2 (see all)

- 2024 Durango Event - 24 February, 2024

- Drive 4 Corners 2022 Low-Key Event Concluded - 1 September, 2022

- Drive 4 Corners 2022 Informal Event Planned! - 6 June, 2022