Article originally posted at http://www.autotraderclassics.com/ and pictures were added from http://www.edmunds.com/

Thirty years ago, BMW shocked the world. Buyers weren’t ready and the M1 bombed, but now the M1 is recognized as one of the greatest driver’s cars to have come from Munich. We pay tribute.

The moment I truly fall in love with the M1 comes early in my drive. The tunnel is empty, long and well lit, and as I enter it I know I’m going to have to floor the throttle. I look across at photographer Tom Salt, grin and lower both windows. Being the experienced old hand that he is, he knows exactly what’s coming next and smiles resignedly.

Initially, I’d not been so passionate about the M1 when it arrived outside BMW Mobile Tradition’s headquarters in Munich. Idling away, ready for action and fuelled-up, it had my name on it for two days.

This is a dream come true for me, and yet…

The reason for my disappointment is simple and slightly shallow: the impact of the Giorgetto Giugiaro-penned body is disguised by the drabbest, flattest, blue paintwork I’ve ever seen gracing a supercar – and it’s at odds with the whole M1 concept. Here’s a model designed to put BMW into the heart of Ferrari road car territory and cut up Porsche on the tracks – and thanks to its dark blue paint job it’s doing all it can to fade into the background, apologetically.

So, it’s down to second impressions then. And they’re all good. Considering that BMW had no supercar heritage when the M1 was conceived, the end result remains fabulous to look at, but that’s probably down to the sheer amount of Italian design input into the M1. It’s squat and purposeful, wide and low, and Giugiaro’s liberal use of slats and louvres in the late-’70s adds considerable interest to what could have been a generic supercar. The engine cover and rear window treatment are especially interesting.

The more superficial styling details delight, too: the way the corporate BMW kidneys are integrated into the nosecone is masterful – and remarkably prescient. Just look at subsequent BMWs, such as the gorgeous 8-Series, to see how much influence the M1 had stylistically. The alloy wheels, too, are delicious, and look as if they have been lifted straight from Giorgetto’s easel.

Under the glassfibre skin, it’s equally interesting – BMW and Lamborghini co-developed a clever box-section steel frame chassis, and Gian Paolo Dallara dialled in the suspension set-up, using his experience gained on the Pirelli P7/Countach project a couple of years earlier.

It’s a shame that this flair isn’t carried through to the interior, though. It’s an all-black affair and, unlike in lesser BMWs, ergonomics are apparently something of an afterthought. The heating and ventilation controls are scattered and their functions – labelled in finest German – are baffling. And, as for the driving position, the clearly calibrated dials are almost entirely masked by the wheel, there’s very little rearward visibility and the pedals are offset to the right. A proper supercar, then.

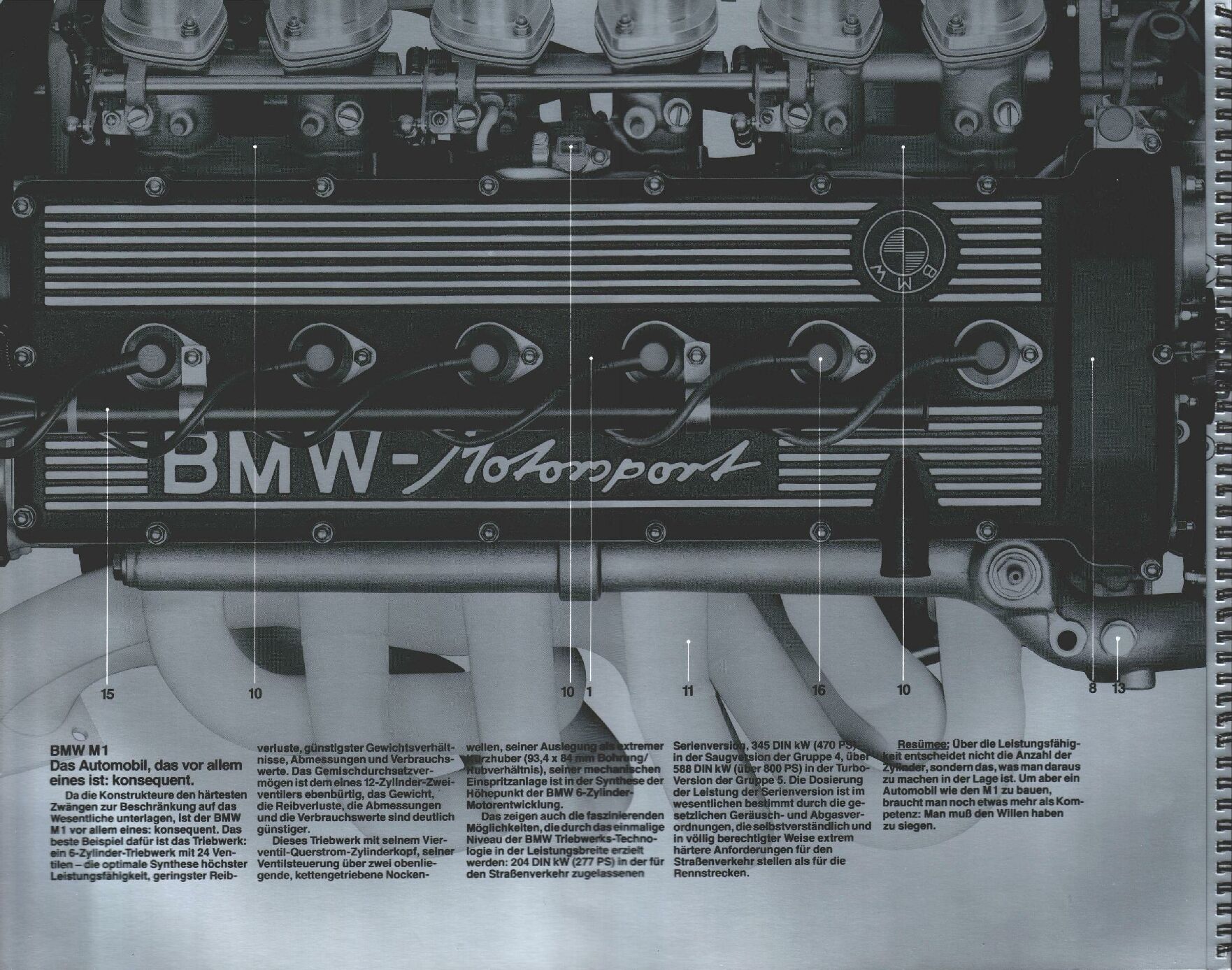

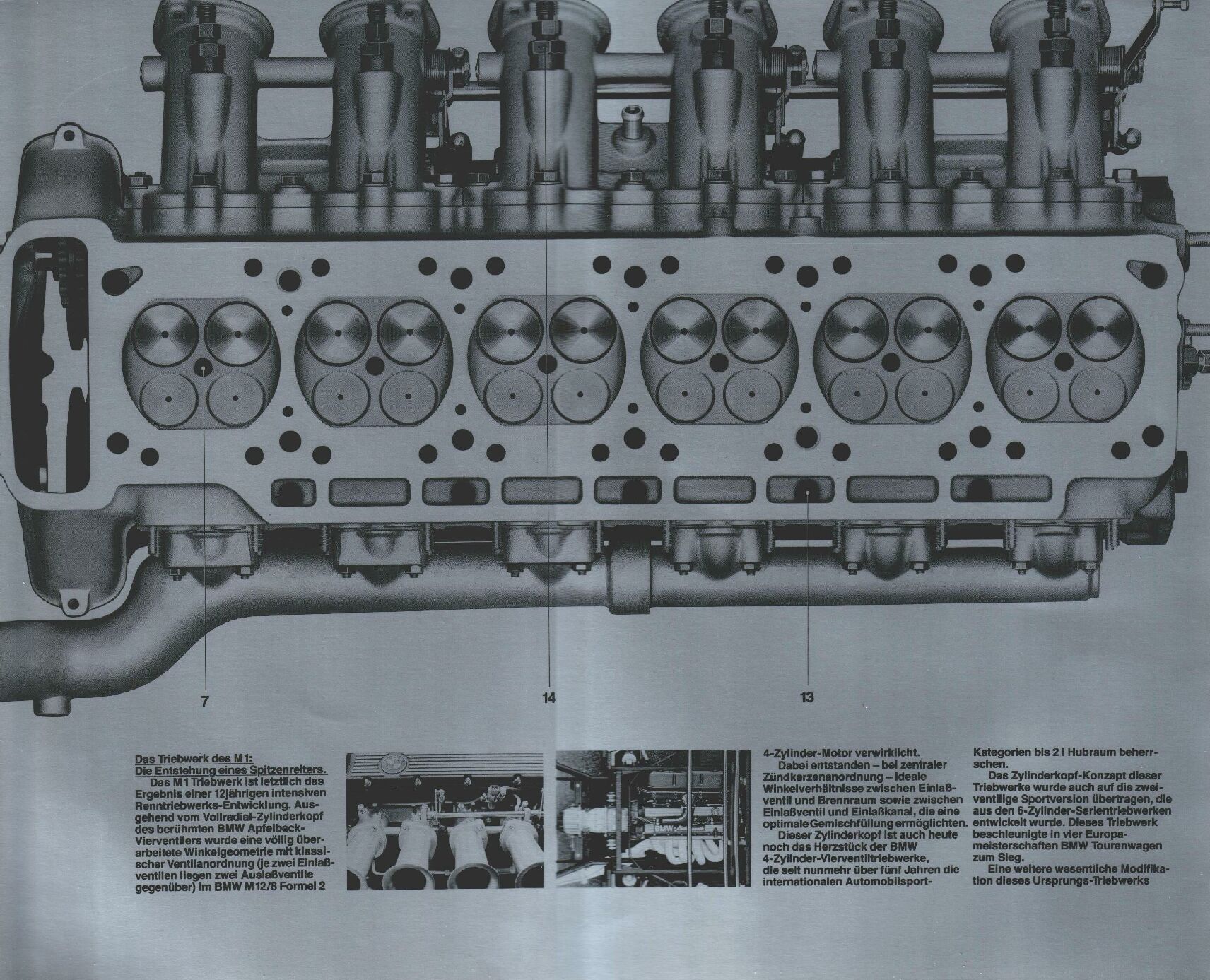

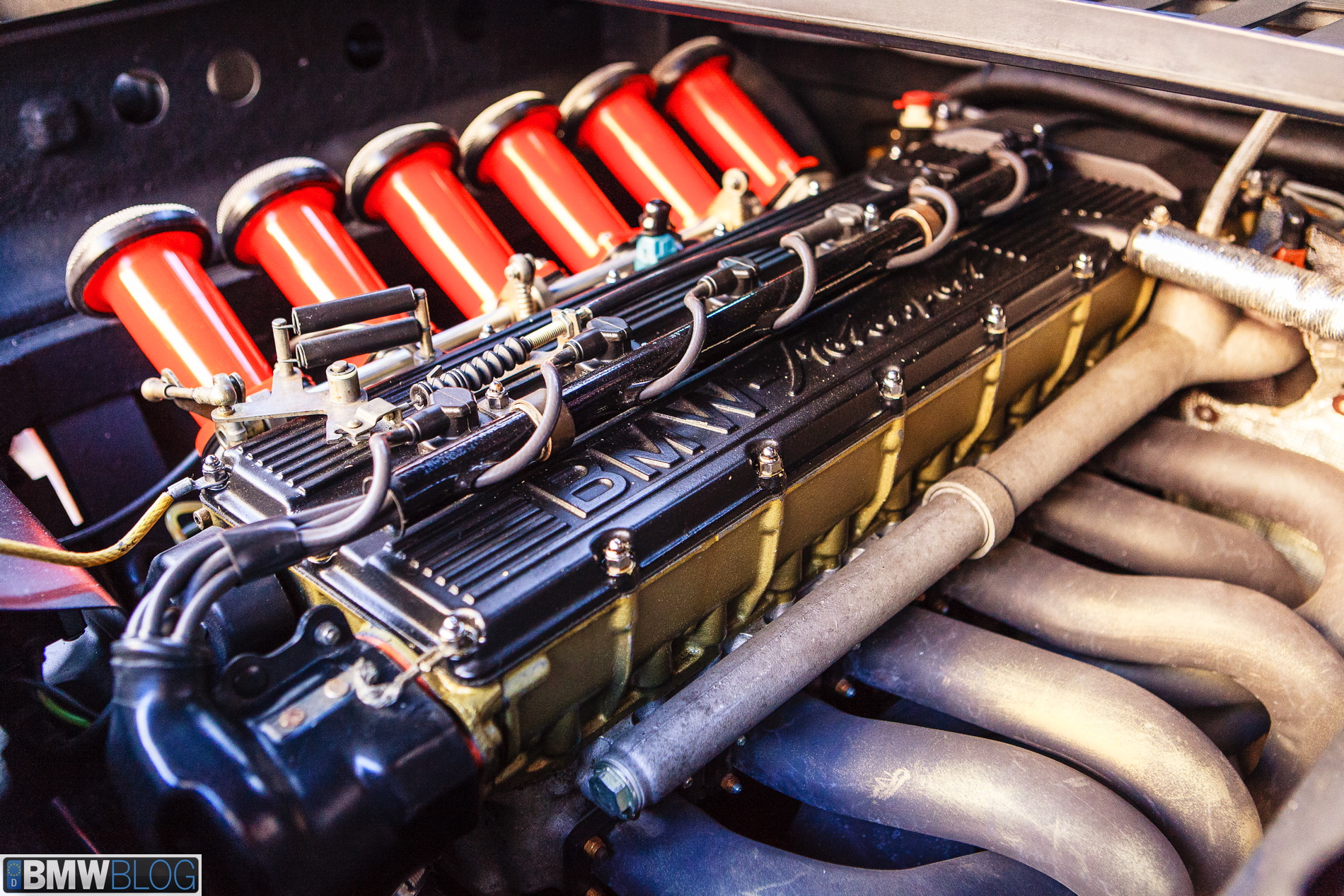

Burbling away at idle, the M88 sounds interesting but hardly special. Supercar engines of this era mostly boasted eight or 12 cylinders, but don’t let this car’s lack of pistons fool you into believing that it isn’t the real deal.

For a power unit conceived in the late-’70s, it’s seriously exotic, featuring a 24-valve cylinder head and a pair of chain-driven camshafts. Kugelfischer fuel injection was allied with six throttle bodies tucked away in individual inlet pipes. The 3.5-litre engine was good enough for 277bhp in road trim, but was boosted to 850bhp for Group 5 racing. Shame that most potential customers saw the BMW’s lack of cylinders as an impediment to true supercar status.

But it isn’t. Setting off – after adjusting to the direct and muscle-buildingly heavy steering – there’s a deep, guttural rasp at low revs that immediately puts me in mind of a trickling Countach. And I like.

Prowling through Munich’s industrial hinterland, it takes time to adjust to the surroundings. The inboard pedals force a driving position that has you naturally angling towards the centre-line of the car, rather than straight ahead, and initially it all feels a little strange. But after a few miles I’ve put it out of my mind, concentrating instead on working around the blindspots, of which there are many. The image in the rear-view mirror is filled with slats, while the door mirrors don’t reveal very much at all – perhaps BMW’s engineers didn’t expect that the M1 would be overtaken by many cars.

But I don’t mind too much. I’m heading for the mountains around Innsbruck and know that, soon enough, I’ll be leaving far behind the city’s wintry greyness.

Considering it was designed primarily for motor sport, the M1 proves surprisingly user-friendly. The dog-leg ’box eases off as temperature builds and, although the change is never what you’d call light, it is positive and a real pleasure to get right. The fact that the pedals are perfectly set up for heel-and-toe downchanges eases the pursuit of right-hand perfection. Low-speed response from the engine is crisp, so there’s no need for high-rev histrionics in order to get away smartly from the lights. In fact, it’s rather easy for a ’70s supercar.

But I’m impatient to see if the M1 is as quick as I hope it’s going to be. And that’s why, when we hit the entry tunnels for the south-bound Autobahn, I’m keen to open the floodgates. With the windows down, and in third gear, I push the accelerator pedal into the carpet. From around 40mph the initial response isn’t thrilling – but there’s plenty of promise. From about 4000rpm the engine note deepens and starts to howl chillingly. From this point on the acceleration is far more purposeful, and in no time we’re kissing the rev limiter and selecting fourth. A tailgating BMW 320d is left far behind, and I’m tempted to carry on… except that we’re limited to 75mph here.

I back off, satisfied that the 277bhp M1 can still cut it in a straight line. When new, BMW’s main target for the car was the Porsche 911 Turbo, which was priced to within a couple of hundred Deutschmarks. But is it as quick?

The delimited signs pop up after we have passed what looks like the last of Munich’s feeder towns, and without even thinking I floor the M1 again, determined to max it. From 80mph in fourth, it still feels quick, but hardly earth-shattering.

The magic 100mph mark passes with ease, although the hardening engine note is becoming increasingly intoxicating. I concentrate and press on. At 125mph I’m into fifth and setting into the final push towards the M1’s maximum speed.

At 140mph it’s getting noisy, the howl from the motor now defeated by wind roar from the A-posts and door-tops. The M1 is also moving around a fair bit, with constant steering input needed to keep the car in its lane. But it’s still pulling feverishly, willing me on… I keep my foot in.

Then, at 150mph in fifth, something unexpected happens: we hit the rev limiter. I look down: 6300rpm is showing on the tacho. That can’t be right. But 150mph it is. The BMW was pulling well and there was more to come, so perhaps the Kugelfischer fuel-injection system needs a tune-up – it certainly feels like a 160mph car.

Disappointed, I rein things in and settle to a 125mph cruise. At this speed the M1 is as capable as any of its contemporaries, and undoubtedly it would have been up there among the Autobahn royalty of 1980.

All too soon, we’re out of Germany and into Austria, homing in on Innsbruck. I’m itching to get up into the mountain peaks that tear into the blue skies above.

Tom has a plan that should have us in the M1’s natural playground shortly. I want snow, and he likes the look of the Jaufenpass just beyond Innsbruck. It’s a 2094-metre high rollercoaster that connects the towns of Meran and Sterzing to the Italian side of the Brenner Pass. Looking at the squiggly line that cuts through Tom’s atlas, it can only mean one thing: playtime.

A quick stop for fuel, and my excitement begins to mount as I know that I’ll be soon giving the M1 a proper work-out in less-than-grippy conditions. Straight-line speed is nice, but feel is what really matters.

Initially, I’m disappointed – there are more cars around than I anticipated, and the snow is so far absent. But little by little, as we climb onwards, the traffic thins, and I start to lean on the M1. It’s time to have fun.

The first thing that strikes me is just how predictable it all is. It’s now well below freezing, the grip levels have dropped markedly, and yet the M1 fails to put a foot wrong. Strong brakes haul the car down faithfully for each hairpin, and handling balance is neutral. There’s very little understeer on entry; nor is there power oversteer on exit with sane throttle inputs.

We continue up the mountain and, finally, the scenery turns wintery white. The roads are now almost completely deserted, and the snow banks either side of the streaming wet ribbon of tarmac remind me that caution needs to be exercised. Conversely, the car is egging me on – its balance and sheer delicacy of response are possibly too confidence-inspiring.

But now the road has opened out more, as the scenery once again changes for the better. The sky is azure, the mountainsides starkly white – and all around me are the jagged peaks that I’ve come to see. I’m now pushing quite hard, experimenting with the grip available, and unsticking the M1 in medium-speed bends is tricky. Using a combination of second and third gears, both perfectly judged for this road, and a few bursts of full throttle reaps so many rewards – and the M1 flows beautifully. It’s a zone I don’t want to leave, but the exhilaration can’t last forever.

All too soon I’m at the top of the Jaufenpass.

It’s only when I climb out of the warm cabin and feel the crisp chill in the air that the majesty of the scenery sinks in.

The winter sun is already setting, casting a pinky hue across the ragged horizon, and the sole thing that separates us from silence is the sound of the engine ticking as it cools off. Part of me wants to stay, but I’m already bursting to clamber back in and attack the downhill run with even more commitment.

The other side of the mountain lacks serious amounts of snow, and the road surface looks bone-dry. I contemplate that as I climb back in – the car is warmed through for a proper run.

Pulling away, I kick the tail out, straighten up and nail it. This section is tighter, meaning I need to use more of the road. In these conditions the M1 feels compact, and as I plunge into the first hairpin I hit the brakes late, turn in smoothly and apply the power earlier than before. The M1 bites me harder than expected, and the tail swings even before the steering unloads, forcing me to apply corrective lock. However, the recovery is rapid, and predictable. Lesson learned – I’ve been playing fast and loose all day; best not push too hard here and now. The nights are cold and dark up here.

I back off and wonder at the M1. Aside from its burdensome unassisted steering and odd driving position, it really is a supercar that you can get in and use on a daily basis. The M1’s range of talents is astonishing, and it stands as a true testament to the benefits of motor sport on road-car development.

All you’ll really need to get the most from it is your own mountain pass, preferably with the odd tunnel thrown in…

http://www.autotraderclassics.com/car-article/M+Powered+original…+_+Driven%3A+BMW+M1-75333.xhtml and pictures were added from http://www.edmunds.com/car-reviews/features/driving-the-bmw-m1.html

downforce22

Latest posts by downforce22 (see all)

- Doppelgänger - 3 February, 2018

- Meeting your Heroes - 16 December, 2015

- Making a Name – The 1992 e36 318is - 12 November, 2015