The M12 engine at full throttle gives off angry shrieks while spitting fire and screaming like a banshee on crack. But when BMW decided to put it in an E21 AND turbocharge it for Group 5 racing, it became something else altogether. The 320 Turbo is a serious contender on any racetrack and sounds the part too.

But before we look at the restored 320 Turbo race car, let’s have a quick look back to learn about out how it came to be. The history and development of the engine alone is a fascinating story, but even more so, is the significance of the M10 and the continued evolution relating to BMW Motorsport.

BMW has a storied history, not only in vehicle production, but in racing with the BMW Motorsports division. It can be argued that the roots of this division go back to the 1960’s with the development of the M10 engine, as used in the BMW E10, or better known “02 series” road cars. This is the car that put BMW back on the map, combining the performance of a peppy engine with a light and nimble chassis; a combination that effectively coined the designation of ‘sports sedan.’

Ultimately, the 02 series was a great success; in the form of both sales and racing success. The powerplant was reliable and popular, with over 3.5 million produced in total over the course of a 20 year production. The ingenuity behind the block was that, from a starting capacity of 1499cc, it was cast within tolerances that allowed it to be bored out to capacities of up to 1990cc. Thus making it a very flexible unit, useful in a wide variety of chassis including a large array of specifications for the 1500, 1600, 2002, 3 series and 5 series BMW’s of the 60′s, 70′s and 80′s (The M10 made it all the way from the BMW 1500 of 1961 to the 318i E30 of 1985). The sporty nature of its placement in the light chassis of the 1502/1602 brought these cars naturally into the motorsports realm. The ultra rare special editions 1800 TiSA and 2000ti had great racing success in the early 1960’s, being the first touring car to round the Nürburgring-Nordschleife circuit in under ten minutes.

So how does all of this fit in with the BMW E21 320?

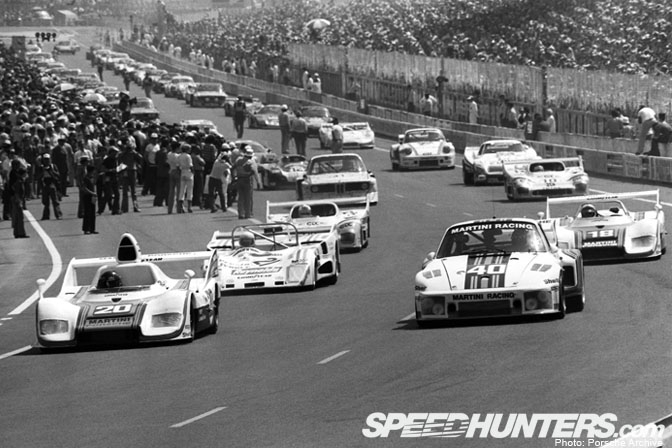

For the 1976 season, the FIA introduced a new Group 5 “Special Production Car” category, allowing extensive modifications to production based vehicles. Cars were built with standard production body widths to meet class requirements, but wide body extensions were added since the regulation of maintaining production body panels only applied to the hood, roof, doors, and rear panel. The highlight of the year was a win at the Daytona 24 hours.

Over in Europe, the Porsche 935 was coming on strong and a new race car would be needed as the outdated 2002’s and CSL’s couldn’t keep pace. BMW had its sights set somewhere else altogether; Motorsport divisions focus shifted away from the World Endurance Championship and to the main priorities; the German DRM Championship and the American IMSA Camel GT series.

To preface, BMW’s decision to get into this series with a new car was in part, due to an additional rule change in Europe. The relaxation of the engine regulations in Formula 2 made the sport more appealing to an increased number of manufacturers back in 1973, including BMW. The base prototype 1.6L engine for the formula cars was expanded to two liters and fitted with four-valve heads, producing over 300 hp (224 kW). So in mid ’76, BMW decided to produce the Group 5 320 for the 1977 season. The lighter E21 chassis (compared to the CSL’s) was to be combined with the successful, powerful and reliable M12 Formula 2 engine with Kugelfischer mechanical fuel injection.

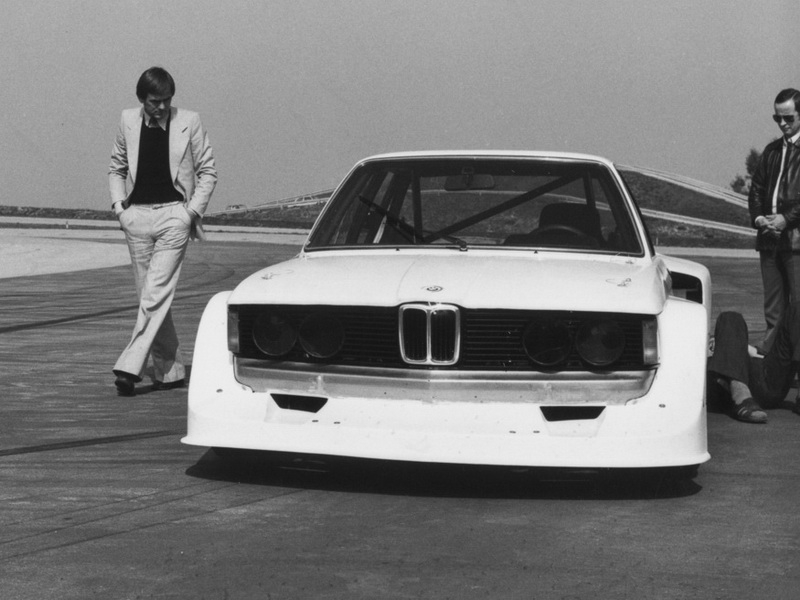

Even though the E21 was a smaller and lighter car than the previous racing CSL’s, further weight reductions and balance improvements were made using lighter materials like aluminum in the suspension along with fiberglass doors, hood, trunk lid and fenders. The end result that BMW presented in December 1976 was a racecar that weighed 740 kgs (1630lbs) including the driver and 60 liters of fuel. It also boasted a perfect 50/50 weight distribution and 304 BHP at 9,250 rpm! This new combination would be the debut of a racing 3 series, and a long genealogy of racing success.

BMW Motorsport manager Jochen Neerpasch had more up his sleeve, presenting the successful Formula 3 drivers Eddie Cheever, Marc Surer and Manfred Winkelhock to complete the fresh new “BMW Junior Team” for the European DRM. He definitely had an eye for talent, as these drivers would all end up in Formula 1, and the BMW Junior Team became the epitome of developing young talent by laying the foundation for BMW’s intensive talent development program.

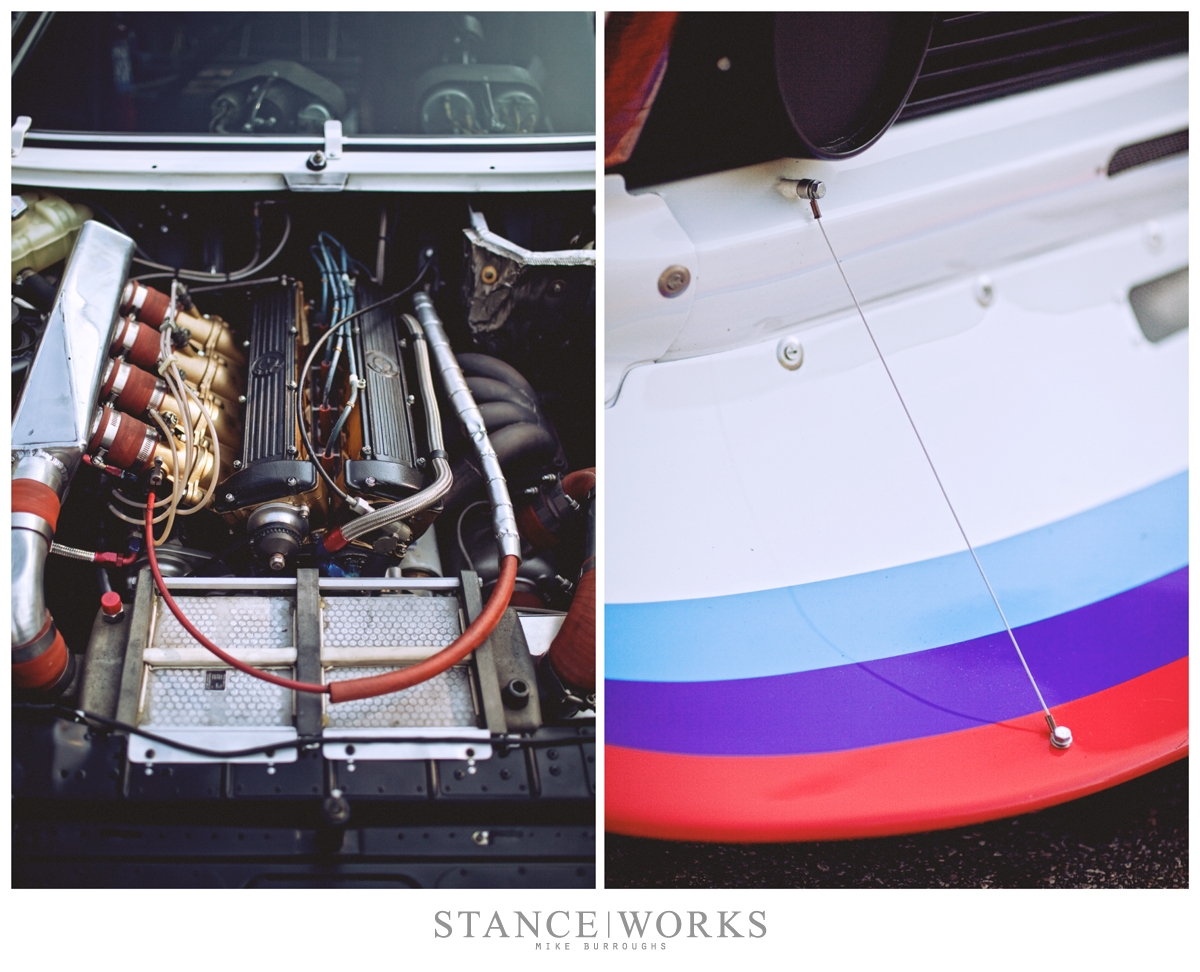

These new cars and promising young drivers were presented in a similar BMW Motorsport striped livery of the infamous red, blue and purple colors used on the racing E9 CSL’s. The three exclusively painted cars for the BMW Junior Team were the main topic of discussion during their first race at the Belgian Grand Prix racetrack in Zolder on March 13, 1977 in the DRM.

When Marc Surer from Switzerland, went on to win the race, the sensation was perfect; the BMW 3 Series had got off to a storybook start on the racetrack. At well over 350 hp (261 kW) from the beginning, it rendered the normally aspirated engines in the two liter category useless. Any relevant competition to the 320 was nowhere to be found so the Junior team of drivers fought against each other, often times destroying each others cars in the heat of the battle.

Also racing at the time was the team of BMW Gentlemen drivers; David Hobbs, Hans Stück and Ronnie Peterson. These veterans were to show the kids the ropes as well as the tricks of the trade, as they were the counterpart co-drivers for a couple of races during the 1977 season. Rumors have it that the gentleman driver’s were guilty of much the same competition, although there wasn’t as much physical incriminating proof.

The 320’s were a force to be reckoned with in the 2 liter DRM class, but the cars rarely raced head to head against the successful Porsche 935’s, since the 320’s competed in division 2 (comprised of 2L or smaller engines). The BMW Junior Team, drove to a dominant eight victories and made the non-turbo versions famous in the 1977 German Racing Championships.

In 1978, BMW’s naturally aspirated 320i’s competed both in the German DRM championship and the World Touring Car Championship. Hans Stuck and Ronnie Peterson drove a naturally aspirated 320, adorned in the infamous Jägermeister orange livery.

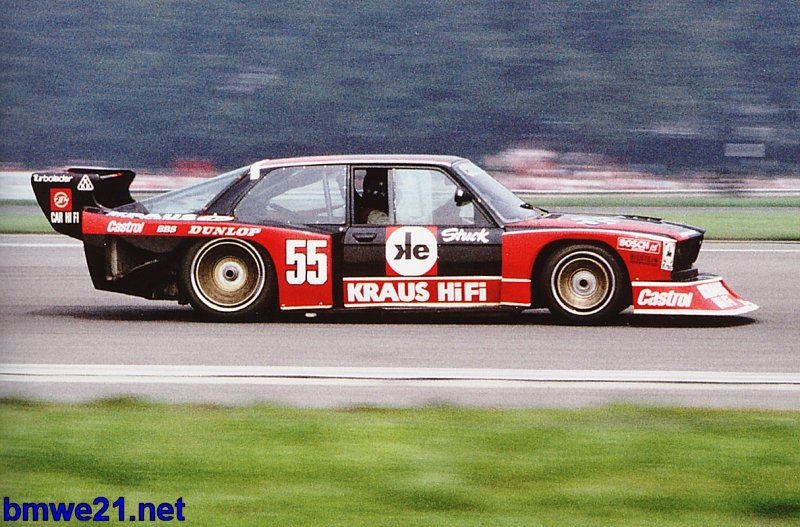

In the DRM, a 1400 cc variant (with a 1.4 handicap factor equal to 2000cc) was turbocharged by Paul Rosche according to FIA Group 5 rules. Third places overall were the common picture, but the cars absolutely dominated the 2 liter class once again. BMW produced 28 racecars, and most of them were supplied to tuners as kits. BMW Motorsport sold Group 5 kits to private teams who wished to campaign their own flame spitting 320 Turbo in a racing series. Seen below are the BMW 320 national teams.

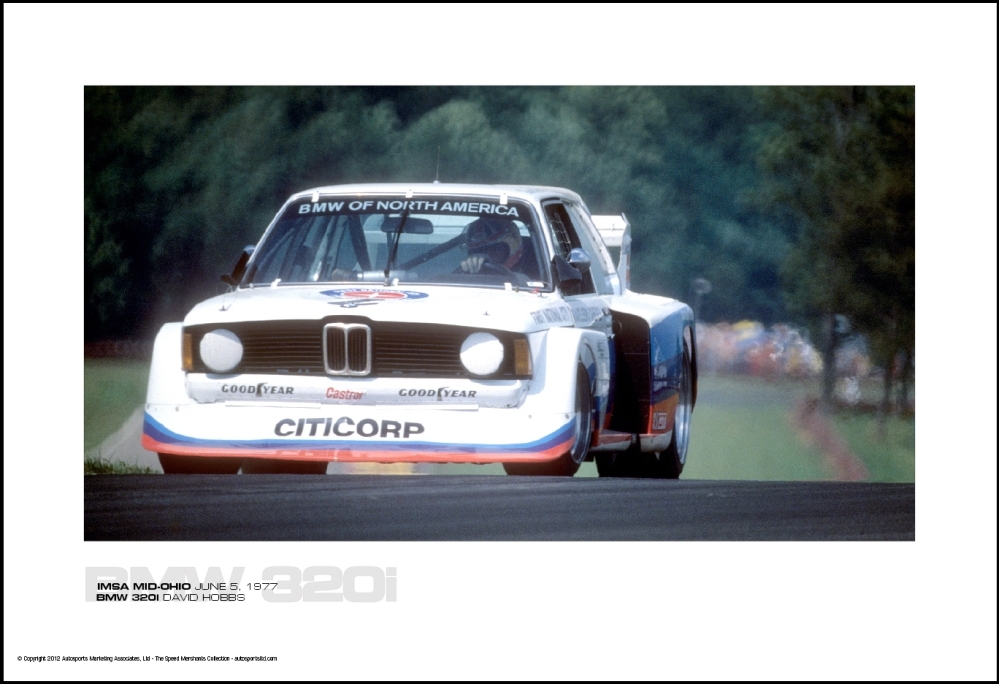

Only a single 320 was to be raced in North America, by the likes of David Hobbs, Ronnie Peterson and Sam Posey. It was this team which BMW North America charged with running its IMSA Camel GT campaigns for the ’77, ’78 and ’79 racing seasons.

With the exception of the shared World Championship rounds, IMSA did not allow the successful 935’s to race in the 1977 Camel GT season, so instead, the new 320 would only have to face off against the 935′s older brother; the 934.

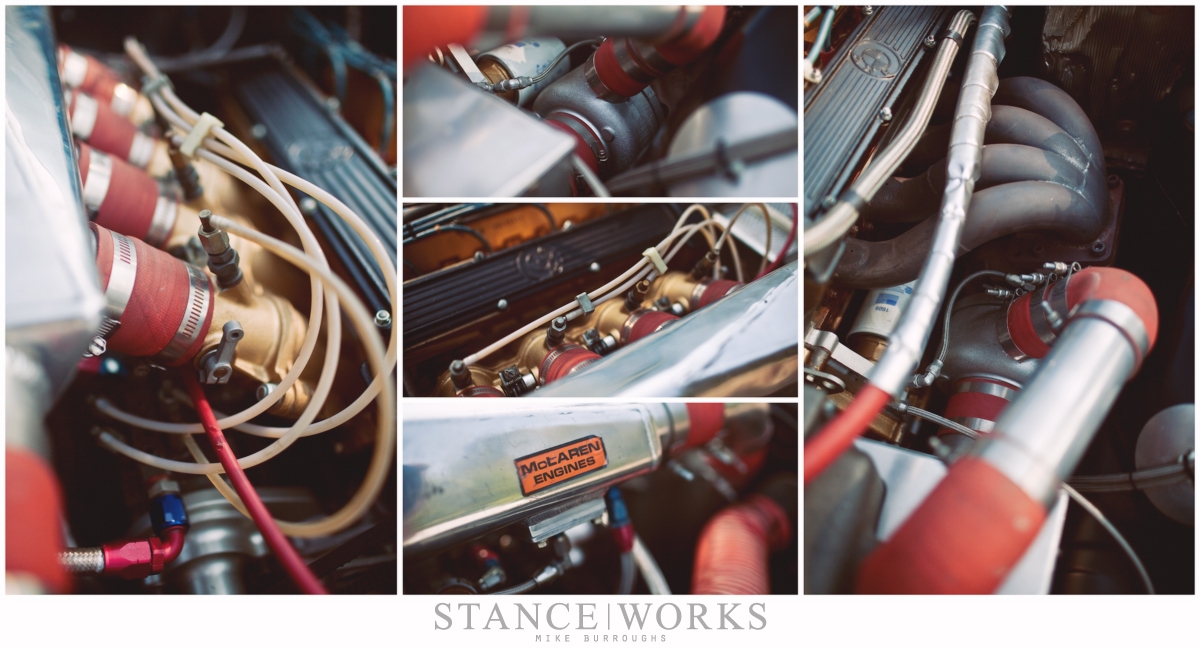

The naturally aspirated 320’s started off being no competition to Porsche’s turbocharged models and so BMW ordered McLaren North America to build a turbocharged version. Now in the 4th generation of the M12 engine, and with the aid of McLaren, the car was fitted with a KKK turbocharger, and thus the 320 Turbo was born.

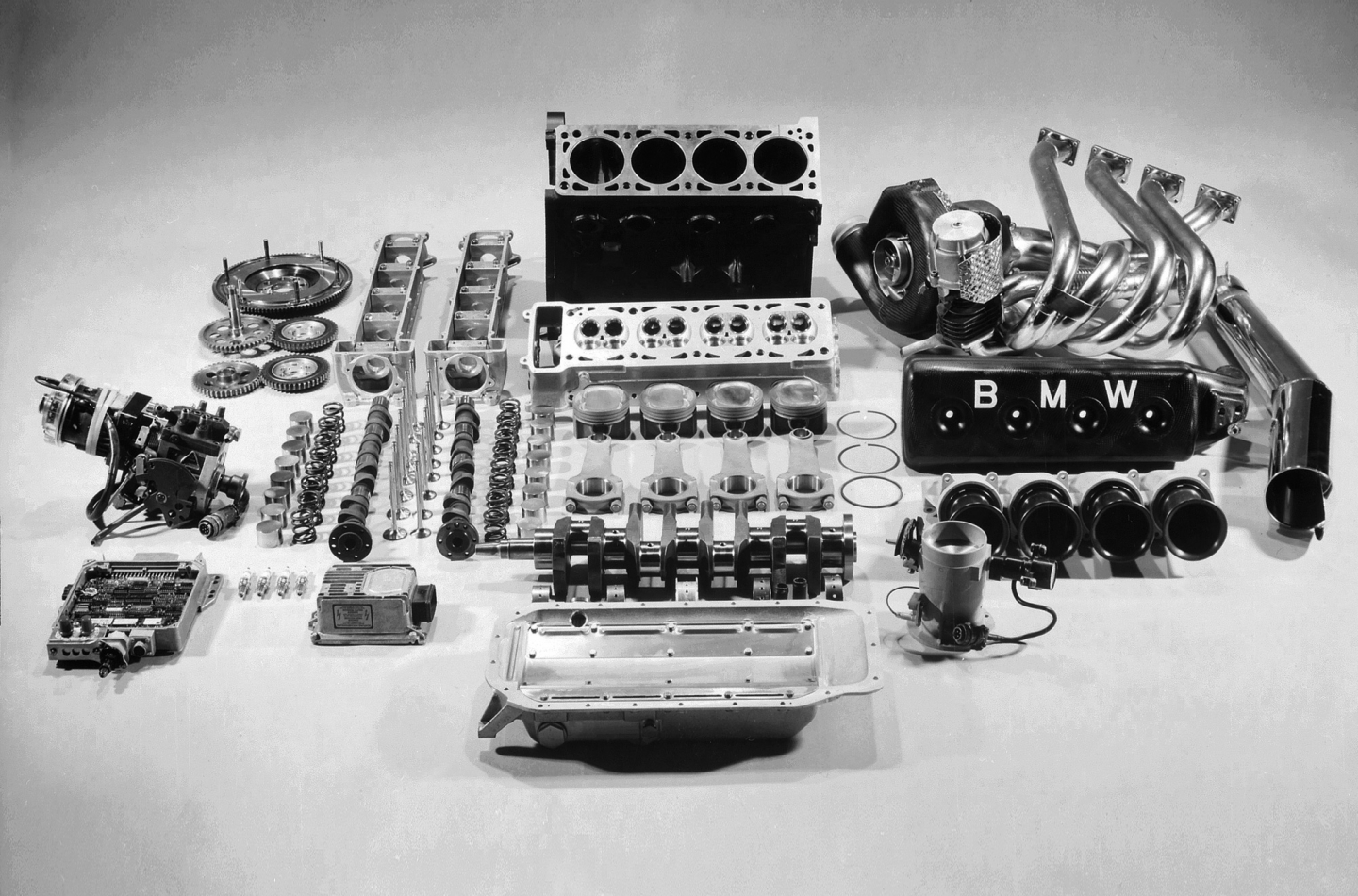

The engine generated a whopping 650 horsepower. The venerable BMW M12/7 racing engine was used in both Touring Cars (320’s – GS Tuning, Heidegger and others) as well as Formula 2. Sixteen valve cylinder head, slide throttle fuel injection (Bosch/Kugelfischer).

They had gear driven cams, typically used Titanium connecting rods, dry-sump oiling – the works. Peak power was made from about 7,000 RPM all the way to 10,000 RPM. The M12/7 was always run vertically (straight up and down) as it was developed for formula car use initially.

The turbo versions of these cars were raced in both Europe and the United States; the European turbo cars had 1.5-liter engines while the U.S. version had the 2.0-liter engine. The 320 sat out of Sebring while the turbo system was fitted, and next appeared at the Road Atlanta 100 Mile sprint race. You’ll notice that front headlights by this stage had now been converted to twin headlights, one of the telltale differences.

The car suffered from a lack of power at low speed, but could give more than 600hp at top-end. David Hobbs had to push it hard, and he really knew how to do it! Nicknamed The Flying Brick, it was damn fast! McLaren had added cooling systems for both oil and water. New plugs and rings had been installed to handle the horsepower. David Hobbs took the start from the back of the field to finish an impressive fourth overall. Many will of course recognize David Hobbs as one of the F1 commentators from Speed TV. Here’s what he looked like back in the day.

The next race at Laguna Seca was even more promising, with David Hobbs starting from the pole. For the race, David Hobbs led the first few laps but then was slowed by the plugs leading to a misfire and eventual retirement. The next race, held at Mid America, was much the same due to an injector issue. The following race Lime Rock saw David Hobbs hold second place in the race behind Al Holbert’s Chevrolet Monza. Unfortunately, a broken fuel line sidelined him once again, only three laps from the finish.

The next race was a turning point in the car’s recognition as a true winner. David Hobbs won his first race of the season, fighting through the challenge presented by Danny Ongais’s 934 Porsche at Mid-Ohio. David Hobbs passed him and cruised to a well deserved victory. Mark Windecker from Speedhunters was on hand to witness the start of the 3 hours of Mid Ohio on August 28, 1977. You can see the lone BMW had to face off against a train of RSRs, 934s, 934-5s as well as Al Holbert’s 1976 IMSA Championship winning DeKon Monza.

Later that year over in Europe, this car was driven by Hobbs and Peterson in the Mosport 6 hours, accompanied by a 2nd turbocharged car built in Munich. The car was driven by Formula One newcomer Gilles Villeneuve and Eddie Cheever and finished 3rd after two 934’s. When these two Porsches were disqualified for not meeting race class regulations, Villeneuve and Cheever ended up winning the race.

The next IMSA race, at Brainerd, could have been the same, but after leading the race when he switched for rain tires before everyone, the car had to retire due to the gearbox and differential issues. By this point in the year, the 320 Turbo was getting a reputation for being fast but fragile. Overall, the turbocharged cars lacked reliability, sometimes having multiple engines fail over the course of the race weekend. The BMW was always in the hunt for pole position, and if it didn’t DNF, it would have a shot at victory. Hobbs was able to live with the Porsches on pace, but unfortunately the car just wasn’t as reliable, with multiple DNF’s (mainly due to engine vibrations that wiggled fuel lines and other parts loose).

Hobbs had already taken outright victories at the Mid Ohio 100 Miles earlier in the season. He dominated at Sears Point Raceway, leading every lap of the race, and managing to squeeze back to back victories at Laguna Seca and Road Atlanta towards the end of season. The race at Road Atlanta proved that the 320 was true contender. It was the first time that Al Holbert was beaten at “his” track, and was probably the most convincing win of the year. An additional win at Hallet Lake netted Hobbs fourth in the Camel GT driver’s championship, although it was Al Holbert, in the Monza, who was crowned driver’s champion for the second year running.

New for the 1978 season however, a new force was coming to IMSA: the Porsche 935 “Moby Dick.” Loophole after loophole was exploited: stretching a rule regarding fender flares to chop off the car’s headlights and reduce drag; double-layering bodywork to satisfy regulations mandating the presence of stock panels. Early 935’s gave FIA officials kittens, but they were technically legal, and no one could stop them from winning. In order to accommodate these cars, a new class was created; GTX. The BMW 320 was also reclassified to run against these mighty 935’s.

The 935 at this stage was THE chassis to have in IMSA, and an increasing number of chassis entered the series as a result. BMW countered with a new lightweight car which featured a tube chassis front end and one piece front body work. The BMW did have some advantages over the 935’s though. It was much lighter, coming in at 875 kg (1930lbs) to the 935′s 970 kg (2140lb) weight and was noted for having superior braking abilities.

The BMW did compete with the Porsches, although having one car made it difficult to challenge consistently. Qualifying for the 1978 race at Sebring was notable, with David Hobbs shattering the previous lap record by twelve seconds; the second fastest car (Porsche 935) was two seconds per lap slower.

The 1978 IMSA racing season, however, will always be remembered as the year of Peter Gregg who took nine victories on his way to the driver’s title in the #59 Brumos Porshe 935. His days with BMW in the CSL were over, and he is better known as a Porsche racing icon.

The Turbo 320 was able to take podiums at Road Atlanta (twice), Brainerd, Lime Rock Park and Laguna Seca which was good enough for David Hobbs to finish fifth at the end of the year. Photos such as this highlight the BMW in its David vs Goliath struggle against the hoards of Porsches.

For a race, Hobbs was even joined by sports car legend Derek Bell. Unfortunately by this stage, the BMW 320 Turbo was at the end of its road as a successful race car. Unlike the previous season, the team chose not to enter the enduros, concentrating on the shorter events only. 1979 ended in similar fashion as the prior year, with Peter Gregg taking another title in the Brumos Porsche, this time with 8 wins.

The BMW’s got a fair share of wins but were never able to clinch the overall title. BMW Motorsport shifted its attention to the larger touring cars, the development of the M1 (using a six cylinder version of the M12 engine), and of course Formula 1. BMW North America did not jump into a full racing program with the 320, and retrospectively, it seems that the car could have been a real winner, would it have had more support. As David Hobbs put it later, it seemed that BMW Germany did not bring great support to the team. The arrival of the M1 was at stake, Jochen Neerpasch (head of BMW Motorsport) thinking that this future car would be a success, decided to focus efforts on its’ development. After all, in its debut late that year, it had finished 3rd at Mid-Ohio, garnering great hope for the new flagships’ use in group 5 (although it later went on solely for the M1 Pro Car series).

The story of the 320 Turbo would end as quickly as it began, with the program ending and BMW North America moving forward with the promising new BMW M1. The McLaren BMW 320 Turbo will be remembered as one of the few cars that was able to challenge the might of the early Porsche 935’s and occasionally beat them at their own game. It had sinister arched flares, and an impressive power plant that set records in a Porsche dominated field. This car deserves a spot in the record books for the trail that it blazed in BMW motor racing history. After all, it was the start of a long 3 series racing lineage, and it was the tip of the iceberg for BMW Motorsport racing success.

The BMW-owned U.S. version of the 320 turbo, was campaigned by Team McLaren and driven by David Hobbs to 7 total wins in the IMSA Camel GT series in 1977 and 1978. It was the first racing BMW 3 series, and left a solid impression for BMW in American racing. It started the trail to stardom for the new E30 BMW and still to be released first generation BMW M3.

This specific car is the special “light weight” car introduced by Team McLaren in late May of 1978 to compete against the Porsche 935s that dominated the grids. It is the very same car where, in its second race, David Hobbs took the pole position and went on to win at Sears Point. This car is over 200 lbs lighter than the previous model with more power, bigger brakes, and better aerodynamics. Hobbs campaigned the car in the remaining 1978 IMSA races and in all of the 1979 IMSA races scoring 3 first place finishes in the IMSA Championship. The car is a time machine and is in “as-raced” condition from 1979, with a rebuilt engine.

This is one of only three chassis used by McLaren USA. BMW North America had the foresight to keep ownership of the chassis in the decades since the 320 Turbo finished its racing career.

This sloping fender was introduced during the car’s second race season in 1978. It is thought to duct additional air into the rear for engine cooling.

You’ll notice one element which is quite different from the Junior team cars is the use of a large 19 inch rear wheel, something which the restored car lacks unfortunately. It’s interesting to note that the huge 19″ rear tires the car used to race with are no longer manufactured and are impossible to source new, so this 320 has been fitted with narrower rears.

You can see under the wild bodywork that the original body is still present.

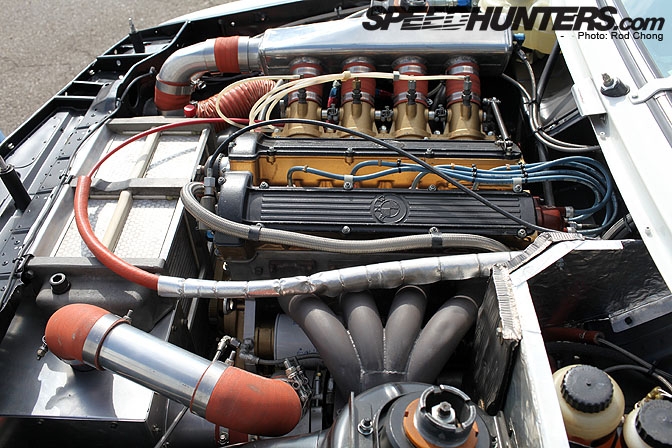

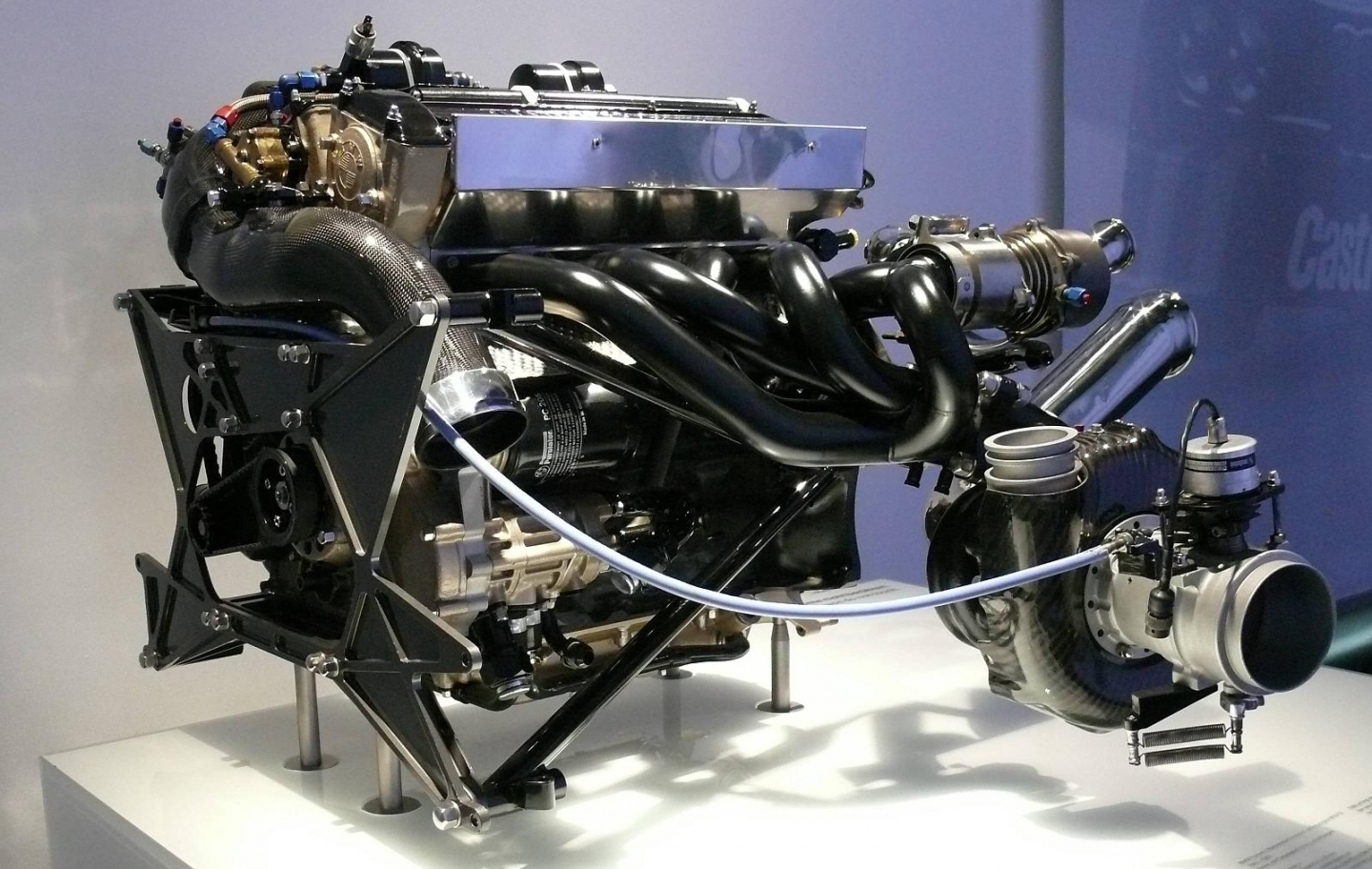

Taking off the regulation E21 hood reveals the jewel of the 320; the turbocharged M12.

Derived from the standard production M10 block, and later used to power the Brabham Bt52 to victory in 1983, power was quoted at 650 hp @ 9,000 rpm although more was potential lurking, as evidenced by the BT52.

The turbo is routed through a fairly sizeable air to air intercooler. If you look closely at the front of the turbo you can see it’s connected to an air box. This was pretty slick stuff back then, as other Group 5 BMWs from this period didn’t have this setup. This technology was a bit new back then and was the first time that big power turbo cars were starting to emerge on to the world’s race tracks.

Those who could master the tech and produce the power reliably, were the ones who converted outright speed into race wins. The air comes in one of these ducts at the front of the car into the turbo.

With the area in front of the engine devoted to the intercooler setup, all oil and water coolers are placed in the rear wide-body fenders.

This means that a fair amount of water and oil plumbing is routed through the interior of the car.

There aren’t many electronics to be seen as compared to the race cars of today. However, this car was the cutting edge of technology back when it came out; utilizing the new formula 1 engine and associated turbocharging technology.

To the right of the driver is command central. Note that the boost knob has been mysteriously removed. Maybe BMW N.A. doesn’t want anyone putting the car into high boost mode. After all, how many M12 engines are still around today, and how many of those can be parted out as organ donors? (The answer is very few)

A channel has been built into the back of the car to get the battery, fuel cell, and fire extinguisher sitting below the chassis floor. The goal was to get the center of gravity as low as possible and it’s interesting to see the length that BMW went to ensure this.

Race History of Chassis 003

1978 IMSA

- Lime Rock – Hobbs, DNF

- Sears Point – Hobbs, Pole Position 1

- Mid Ohio Hobbs – Klausler, 2

- Road Atlanta – Hobbs, 24

1979 IMSA

- Road Atlanta – Hobbs, 6

- Riverside – Hobbs, 38

- Laguna Seca – Hobbs, 2

- Hallett – Hobbs, 1

- Lime Rock – Hobbs, 2

- Brainerd – Hobbs, 2

- Mid Ohio – Hobbs/Bell, 9

- Sears Point – Hobbs, 24

- Portland – Hobbs, DNF

- Road America 500 – Hobbs/Bell, 1

- Road Atlanta – Hobbs, 3

In the years that followed, the engines developed steadily, mainly focusing on Formula racing with the 1.4 Liter engine. Significantly, the 320 turbo engine was the test bed for the BMW Brabham BT52 that took Nelson Piquet to the 1983 Formula 1 World Championship. The M12 race engine was based on the production M10 engine block as introduced in 1961, and it had great racing success. This engine formed the basis of the M12/13 design, the race unit that BMW ultimately supplied around the world in the 80’s.

It powered the F1 cars of Brabham, Arrows, Benetton and won the world championship in 1983. It also powered the BMW GTP and in the 2.0 liter naturally aspirated form, the successful March Engineering Formula Two cars. This 4 cylinder engine saw it become the measure of all things formula, and was by far the most powerful F1 engine of all time. It ran 5.5 bar (80psi!!) of boost during qualifying in the Brabham BT55 in 1986, resulting in 1400 bhp. In later versions, the engines were tilted 72 degrees to lower the weight in the chassis. The biggest problem was they tripled their horsepower within a 1000rpm rev range making them extremely hard to drive. They suffered dramatically from reliability issues, and didn’t garner any success, forcing BMW to pull out of F1 altogether by the end of 1987 and giving meaning to the saying “the candle that burns twice as bright only burns for half as long.”

There is no F1 engine that has ever been able to match or beat this and probably never will. Gordon Murray, who designed a number of the BMW Brabham’s and later, the more well known monster McLaren F1 road car, was quoted as saying he designed the Brabham BMW BT55 F1 cars with 70% of the weight over the rear wheels because there was no way he could get all the power to the ground any other way. These were only 1.5 liter, 4 cylinder road going BMW engines, remember. And if you believe the reports from Bavarian engineers at the time, some of these blocks were apparently being pulled straight out of road cars with over 100,000 km’s on the clock. Folklore tells us M10 engine blocks were also reportedly weathered in the rain and urinated on by mechanics prior to becoming 1400 HP banshees.

Just in case you didn’t understand this engine’s superiority, Gerhard Berger still holds the all time record for the fastest speed ever recorded in an F1 car on circuit at just over 350kph (217mph). Made from a block cast in the 60′s.

Megatron, as the engine is most commonly known (being purchased for use from BMW), was the last iteration of this engine development. The old BMW 4-cylinder turbocharged engines being bought from BMW Motorsport and prepared in Switzerland by Heini Mader. These were badged Megatron and were used to power the Arrows A10 in 1987.

The BMW M12/13 turbo engine is the most powerful race engine ever produced by BMW and, from a racing perspective, one of the most successful engines in racing history. The racing success is unparalleled, and even has links to the basis of the design in the E30 M3; as the Formula 2 M12 was also the basis for the highly successful BMW M3 Group A touring car, you know, the one with the title of the “most victorious racing car of all time.” Incredibly, the block of that car was also based on the venerable M10, and the head was an evolution of the M88 engine (M1) with two cylinders removed. That car alone garnered 1,436 victories in just 1,628 days.

So it is strikingly obvious that the use of the M10 engine block from the early sixties made a huge mark on BMW motorsports. The little 1502 that established BMW as a global force, also directly shared it’s engine internals with the 1400hp fire-breathing Brabham BT52 and laid the groundwork for the S14 in the E30 M3 and BMW Motorsport as we know it today. The pathway of continued evolution for this engine led BMW from the 02 series of cars to the M1, Brabham Bt52/Bt55, and eventually to the birth of a legend, in the 1988 BMW M3.

The M12’s placement in the E21 320 racecars was just a stepping stone along the development path of this storied engine, and BMW motorsport success. Next to the twin Turbo Porsche’s 935′s and Zakspeed Capri Turbo’s the BMW 320 Turbo was part of one of the most exiting racing series that ever raced the globe, and so making it one of the most famous race cars in the history of BMW Motorsport. Nowadays, racing simulators are about as close as we can come to the real thing.

It’s a real shame BMW doesn’t make raw machines such as this one anymore…

While every effort has been made to render as accurate as possible details regarding the history of these cars, inaccuracies may have occurred. Please help us fix these inaccuracies by replying in the comments section.

Sources:

http://www.bmw1800ti.writernetwork.com/catalog.html

http://www.supercars.net/cars/3820.html

http://alex62.typepad.com/imsablog/2006/05/bmw_320_turbo_t.html

http://www.supercars.net/cars/168.html

http://www.speedhunters.com/2009/09/car_feature_gt_gt_mclaren_bmw_e21_turbo/

http://www.conceptcarz.com/vehicle/z9039/BMW-320-Turbo.aspx

http://www.bmwe21.net/?page_id=496

http://racingotaku.wordpress.com/2009/06/08/best-f1-engine/

Latest posts by Tom Schultz test #2 (see all)

- 2024 Durango Event - 24 February, 2024

- Drive 4 Corners 2022 Low-Key Event Concluded - 1 September, 2022

- Drive 4 Corners 2022 Informal Event Planned! - 6 June, 2022