The BMW marque has an extensive history reaching back before World War II. What many people don’t know is how BMW was able to rebound after the war and that a crucial component of BMW history is hidden in the depths of time. Because of this, not all BMW’s from the time period may be what they seem; it may in fact be a Doppelgänger.

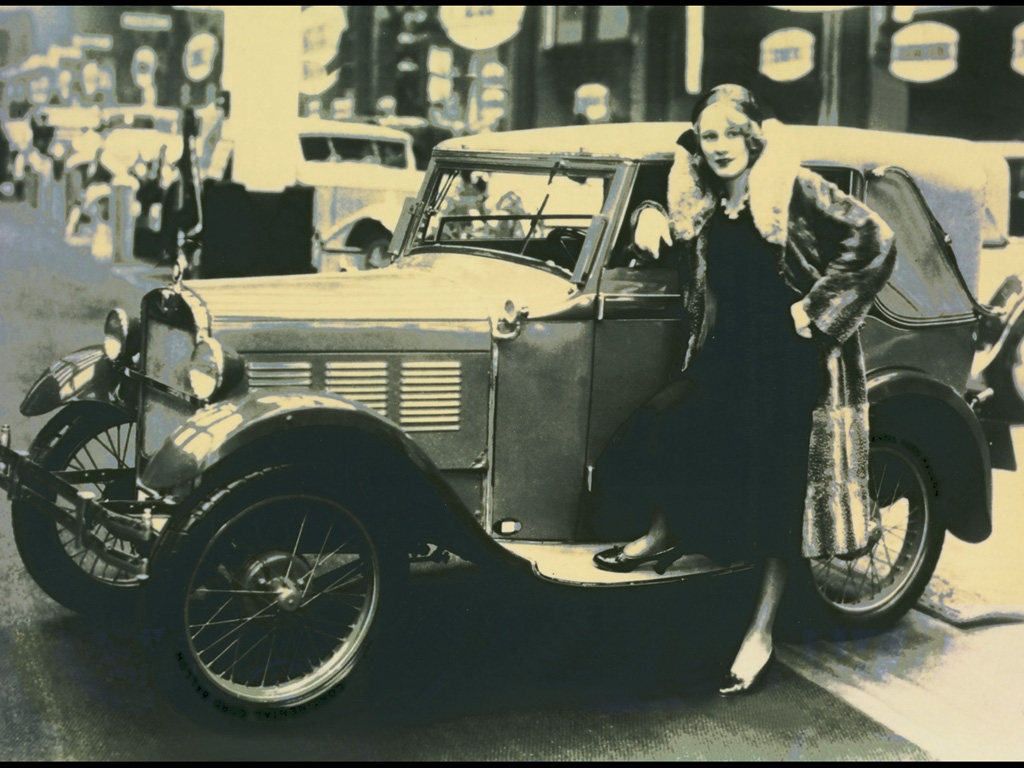

To get a frame of reference, lets delve back to the year 1928 when BMW acquired Eisenach based Dixi Automobil Werke AG. The successful family of cars built by the Dixi Fahrzeugfabrik Eisenach (Dixi Vehicle Factory Eisenach) would attract BMW’s attention in the 1920s, as BMW wanted to diversify into automobiles after having successfully added motorcycle production to its core aviation engine line in the early 1920s.

The Dixi 3/15

After BMW bought the factory–along with the rights to build the Austin Seven-derived Dixi 3/15–in late 1928, Eisenach became its center of automotive production, and this plant was where all BMW cars were built, through the start of WWII. The Dixi would be followed by increasingly sophisticated cars like the 1933 303, which introduced two BMW key features: the inline-six engine and twin-kidney grille. The upscale 326 sedan, introduced in Berlin in 1936, was the basis for an advanced competition/sports car derivative, the 328 roadster, which debuted in June of that year.

The BMW 303

Also 326-based and sharing the basic 2.0-liter overhead-valve inline-six, shorter wheelbase and streamlined styling motifs with the 328, was the beautiful 327 Sport-Cabriolet. This prestige-class car, introduced in November 1937 and bodied by AMBI-Budd in Berlin, enjoyed a small performance boost over the 326, thanks to increased (6.3 vs. 6.0) compression, but it didn’t get the 328’s complex hemispherical combustion chamber cylinder head or triple carburetion. The Sport-Cabriolet was joined by the 327 Sport-Coupe, bodied by Autenrieth in Darmstadt and featuring 2+2 seating, in October 1938. BMW also built a small run of open and closed 327 variants with the 328’s 80-hp engine, calling them 327/28s.

After the firm halted civilian automotive production circa 1940, it turned the Eisenach factory over to building motorcycles and aircraft engines for the German army and air force. As was done to the Milbertshofen factory, Allied bombing raids successfully targeted this plant during the war. When hostilities ceased in 1945, a substantial portion of BMW’s sole automotive facility lay in ruins. The physical damage was almost trivial, though, because of how Germany was divided into zones of occupation: Despite being only about six miles inside the border, Eisenach fell in the Soviet zone, while Munich was solidly in the American. Both factories were ordered dismantled, their dies, tooling and engineering expropriated–and the Milbertshofen plant’s contents would be distributed to as many as 16 different countries. Eisenach would prove a different story, as forward-thinking workers had stashed important tooling in underground bunkers during the war years to save it from air raid damage, and this tooling would become the plant’s lifeline.

Those Eisenach workers were able to keep their factory intact by proving to the newly formed Soviet Military Administration for Germany (SMAD) that they could quickly resume production of prewar BMW cars and motorcycles, which would be used as reparation and for selling in the German Democratic Republic, the Eastern Bloc and the Benelux and Scandinavian markets. The Eisenach works came under control of the Soviet state-owned Awtowelo (a.k.a. Autovelo), which grouped it with other East German component firms, helping to reestablish the supply chains needed to mass-produce vehicles. The Munich plant was not so lucky, and because it was legally barred from vehicle production, began manufacturing things like aluminum cooking utensils, bicycle frames and building materials.

As long as the Soviets owned the company, BMW in Munich could not bring legal proceedings to protect its tradename. As the Munich factory was not producing cars yet, all “BMWs” made from 1945 to 1951 are Eisenach products. The first “BMWs” to roll out of Eisenach, built in 1945 with left-over parts and spares from local dealer stock, were 321s. Carburetors that had been supplied by Solex, transmissions that came from ZF, and other components whose suppliers were now located on the other side of the Iron Curtain, were carbon-copied and made by Eastern suppliers.

The prewar body dies and tooling were brought in-house, and production ramped up; nearly 9,000 321s were manufactured through 1950, along with a handful of 326s. This factory, completely independent of the parent company yet still branding its vehicles as BMWs, developed the 340 from the 326, which it would build in great numbers from 1949 through 1955. Also introduced in 1949 was Eisenach’s version of the prewar 327 Sport-Cabriolet, which it called the 327/2.

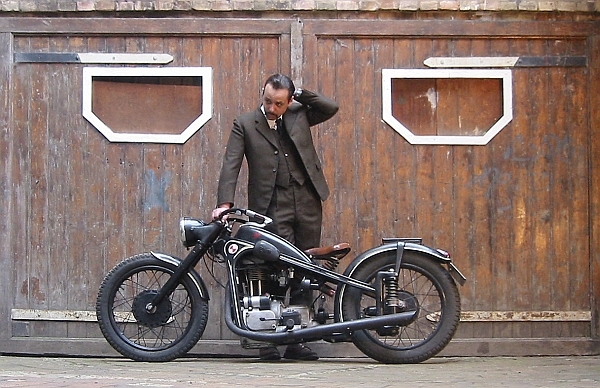

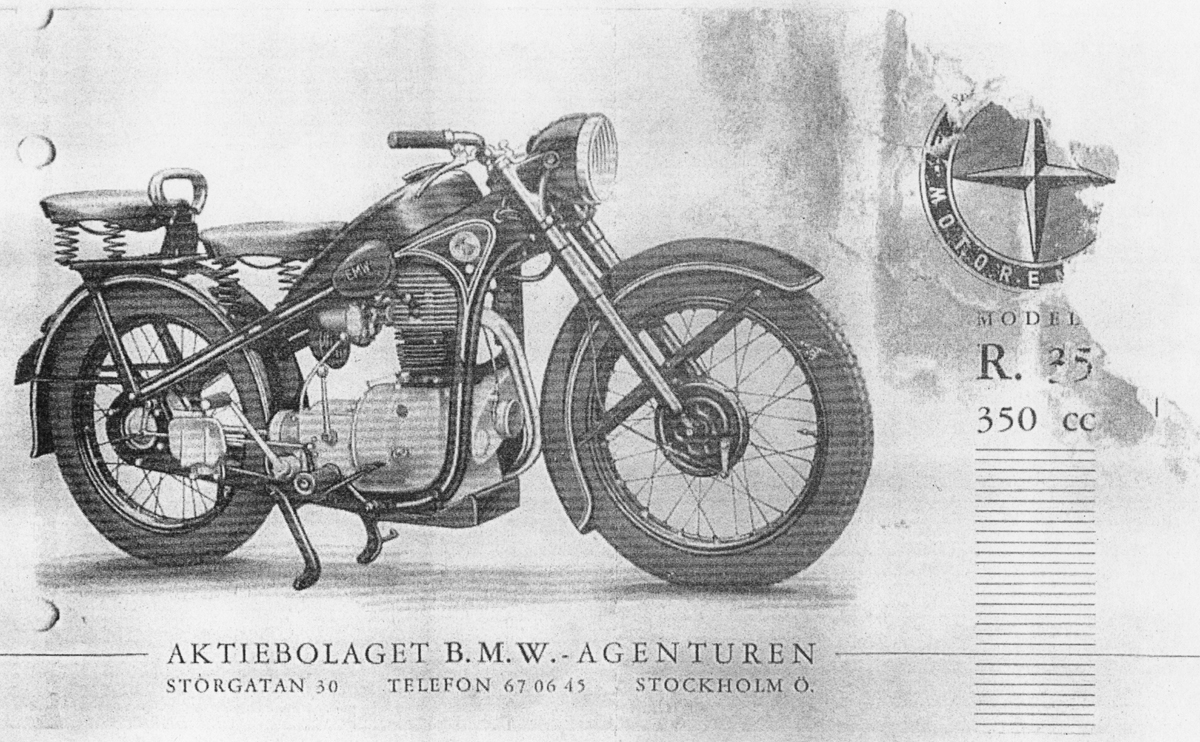

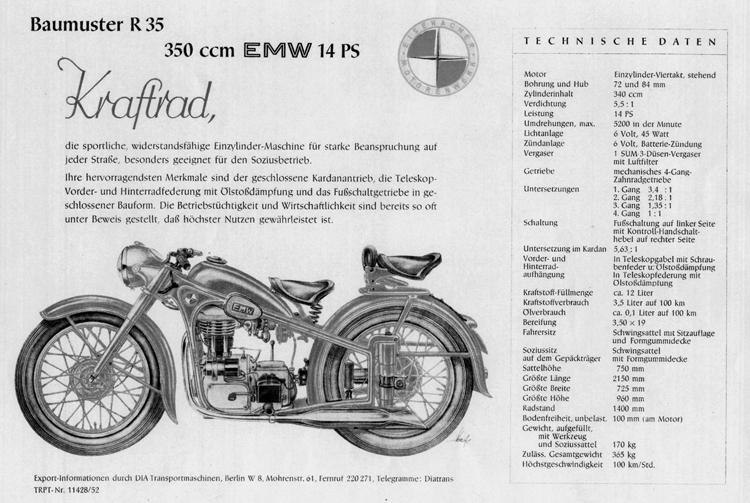

By the time the 340 and 327/2 were on line, the “true” BMW was back, building motorcycles in Munich that, essentially, competed with those coming off the line in East Germany and wearing the same badge. BMW tried to block Awtowelo from selling vehicles using the BMW brand name and logo, and in late 1950, got a legal ruling that Eisenach-built vehicles that were to be sold outside of the GDR could not be branded as BMWs… although it’s doubtful that company was quick to comply. To protect its trademarks, BMW AG legally severed its Eisenach branch from the company. In 1952, the Soviets transferred the Eisenach factory’s ownership to the East German government, and it received a new identity, VEB IFA-Automobilfabrik EMW Eisenach. In short, it was the Eisenacher Motorenwerk/EMW, and some of the cars it would produce would wear a new badge: a slightly-modified roundel whose quadrants were separated with a four-point star, and which replaced Bavaria’s blue with Thuringia’s red.

In 1954, the 327/2 was joined by the 327/3 Sport-Coupe. As it had been in its earlier life, this coupe was a pricey, prestigious car intended for party officials, VIPs and the top end of the export market. It shared most of the “/2” Sport-Cabriolet’s postwar features, including a 340-inspired instrument panel and a redesigned hood that no longer opened with the side panels. The 327/3’s traditional steel-over-wood frame body, which now used a larger one-piece rear window, rather than two smaller panels, was built at VEB Karrosseriewerk Dresden, which was the nationalized version of the venerable Gläser-Karrosseriewerke.

The prewar mechanicals carried over into this new car, and while the names had changed, the song remained the same. The 1,977-cc inline-six engine used two IFA downdraft carburetors–virtual clones of Solex 32s, with interchangeable components–and 6.3 compression to make 57 hp at 3,750 RPM, and the four-speed manual transmission with freewheeling on first and second gears was now built by VEB Fahrzeuggetriebewerk “Wilhelm Friedel” in Karl-Marx-Stadt, rather than ZF. The brakes were four-wheel drums, and the suspension was independent in front (A-arms, transverse leaf spring, hydraulic tube shocks) and live axle in the rear (longitudinal leaf springs, hydraulic tube shocks).

Although official figures don’t exist, it’s believed that 505 327/2 Sport-Cabriolets were built in Eisenach between 1949 and 1955, along with 152 327/3s, which were produced in 1954-1955. One EMW, owned by Rachelle “Rocky” Grady and maintained by her husband, Henry, is considered a late 1954 model, the 144th 327/3 built, and it wears that striking EMW badging.

“Nobody knows how many were built with BMW badging, versus EMW,” Rocky says. “I’ve seen photographs of a car considered postwar, that has the blue and white roundel. We spoke with an expert from BMW in Germany about this, and he confirmed that he wasn’t aware that it was in the United States, and the only other 327/3 he knew existed was in a museum in Munich. We belong to the BMW Vintage & Classic Car Club of America, and while there are a few 327/2 cabriolets here, no other coupes have yet surfaced. I can’t believe there aren’t more stashed in Scandinavia, Belgium or Austria.”

“Prewar cars, in general, drive a bit like trucks,” he interjects with a laugh. “Her steering is relatively light, although there’s no power assist, and the brakes are responsive. Shifting is unusual, since the gates are kind of vague, and first and second gears have a freewheeling function, so when you back off the throttle, it coasts, with no engine braking.”

Other prewar-type features still present on the EMW are the foot pump-operated central lubrication system, which also lubricates the steering rack, and the functional traffic turn signals. “I’ve added a flasher system for turn signals,” he notes. “While the prewar 327/3s had suicide doors, this has conventional front hinges, which make it easier to get into the back seat.” Folding the rear seatback down is the only way to access the trunk, but Rocky reports that there is enough legroom for two smaller adults to sit back there comfortably for short trips. They’re contemplating adding seatbelts to improve road safety.

Mystery and rarity, combined with the car’s immaculate presentation, have made it an attention magnet anywhere they go. While the 327/3 is vintage-style fun on the road, concours and car shows are its natural habitat, Rocky says.

“I wanted to own a car with historical significance, but there’s so much more–she has flawless elegance,” Rocky muses. “I can’t walk by Emma without enjoying the artful way she was designed. She seems to defy any notion of age. It puts a smile on my face, every time.”

BMW was newly back in the car business, building its own prestige models in Munich in 1954, including the V-8-powered 502 “Baroque Angel.” The Albrecht Graf von Goertz-styled 503 and stunning 507 roadster were in the planning stages, to be introduced to a shocked public two years later, so the hand-built-in-tiny-numbers EMW 327/3 was likely of little consequence to its parent company anymore. It may even have been redundant to EMW, as after 1955, the East German company’s name would change to VEB Automobilwerke Eisenach, and its focus would shift from building BMW-derived cars to something very different–a three-cylinder, two-stroke economy car that reintroduced a historic regional nameplate: Wartburg. “Wartburg” derives from the Wartburg Castle on one of the hills overlooking the town of Eisenach.

So if you ever get the chance to see a Post war BMW built before 1951, double check that it is actually a BMW, and not a Doppelgänger.

Specifications of the EMW 327/3

Engine: OHV inline-six, cast-iron block and head

Displacement: 1,977 cc

Bore x stroke: 66 x 96 mm (2.6 x 3.78 in.)

Compression ratio: 6.3:1

Horsepower @ RPM: 57 @ 3,750

Fuel system: Twin IFA 1-bbl. carburetors

Transmission: Synchronized four-speed manual, freewheeling on first and second

Suspension: Front: Dual A-arms with transverse leaf spring, hydraulic shocks; Rear: Live axle, semi-elliptic leaf springs, hydraulic shocks

Steering: Rack and pinion

Brakes: Four-wheel drum

Wheelbase: 108.3 inches

Length: 177.2 inches

Width: 62.9 inches

Height: 55.9 inches

Weight: 2,425 pounds

Top speed: 78 MPH

Efforts have been made that information contained is as accurate as possible. If errors are found, please comment. Original article and enhanced information drawn from wikipedia and Hemming’s march 2015 Doppelganger article.

downforce22

Latest posts by downforce22 (see all)

- Doppelgänger - 3 February, 2018

- Meeting your Heroes - 16 December, 2015

- Making a Name – The 1992 e36 318is - 12 November, 2015