If you haven’t already heard, BMW is launching a new GT Racecar, the 2016 M6 GT3 which replaces the 2010 Z4 GT3 car of the last half decade. The use of the same twin-turbocharged 4.4-liter V-8 fitted to the M6 road car will power the car, albeit with minor improvements. The impressive combination boasts dry sump lubrication and generates up to 585 hp and tips the scales at less than 1,300 kilograms (2860 lbs).

Now almost 80 years after BMW’s racing debut with the 1936 BMW 328 [Click for Part I] prototype, let’s take a look back at the evolution that started such a famed racing heritage for BMW. Is there any chance the new model will be able to replicate the success of 75 years ago?

When the foundations were laid for the construction of the BMW 328 in the early 1930s, the car’s creators Rudolf Schleicher and Fritz Fiedler had little idea of the significance the sporty two-seater would one day attain. Several decades on, this Roadster, with its powerful 2-litre six-cylinder motor, is still lauded as the most beautiful and successful sports car of its time. Schleicher and Fiedler made the ideal engineering team for such a project. In addition to their deep knowledge in many areas of automotive construction, the two men could call on many years of experience, a wealth of ideas and, above all, ambition. They complemented each other perfectly, the engine specialist Schleicher blending his talents with Fiedler’s expertise in vehicle construction to outstanding effect.

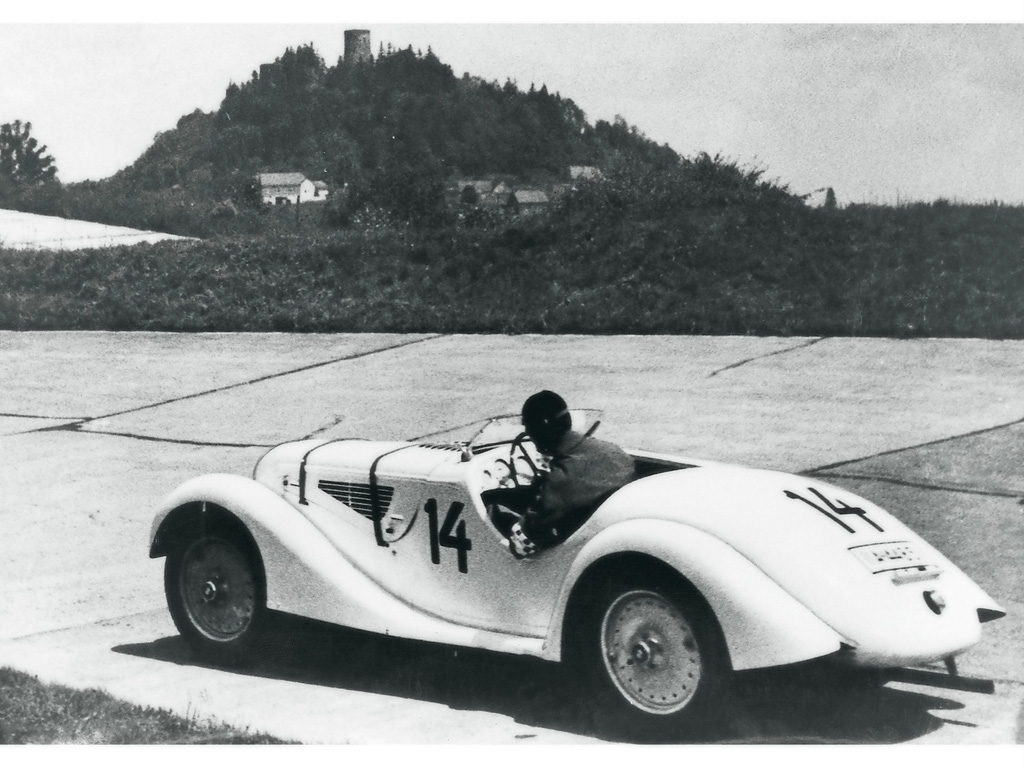

Those early outings with the BMW 328 prototypes on the race track showed design engineers Fiedler and Schleicher that further development work was required for the 328 – when it came to use both on the road and in race action. They began by trying to weed out the weak points that had been so stubbornly apparent during the high-speed race in Montlhéry. At the same time, they set up a racing department to provide a professional platform from which to run the racing activities for the BMW 328. This department also ensured that the knowledge gained in the races would flow into the development of the standard 328 and, indeed, into production of other BMW models as well.

On the road, its top speed of 155 km/h made it one of the quickest cars around. And, with only 464 examples ever made, the BMW 328 is today one of the most sought-after collector’s items on the market. Its allure lies in the timelessly beauty of an open-top two-seater, its still convincing engineering and the aura that countless racing victories had created around it. After all, the BMW 328 was not only one of the most visually appealing sports cars of the pre-war period, in the 1930s it was also the most successful racing machine in Europe.

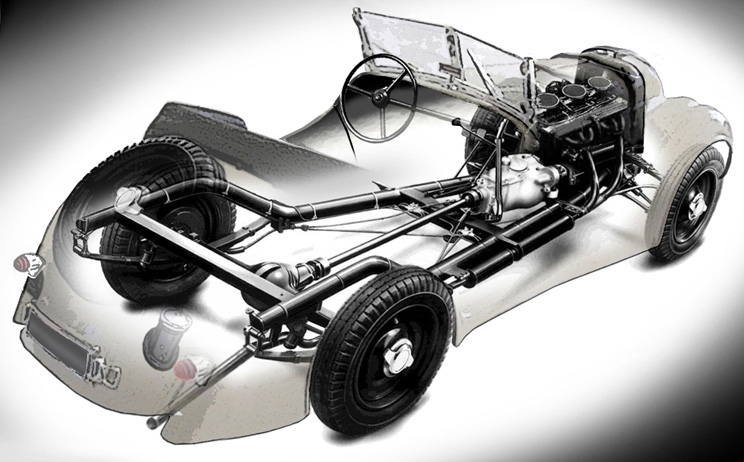

Since its maiden outing in the 1936 Eifel Race, the BMW 328 had quickly established an iron grip over Europe’s race tracks. For the engineers in Munich, however, this was no reason to take their foot off the gas. Instead, they worked continuously at increasing the car’s original output of 80 hp. After all, rival manufacturers had already boosted their engines to something around 110 hp with superchargers and advanced yet complex technologies. There was certainly little scope to further reduce the weight of what was already a lightweight car in standard production form. It was just enough chassis and no more, offering a combination of strength, simplicity, low weight, and for the time, incredible agility and roadholding. At that point, reducing drag seemed like the only way to increase speed and performance. The curvaceous form of the 328, with its prominent front wings, may have been a masterstroke of engineering and design, but it was less than ideal aerodynamically. And so the BMW engineers set about designing a totally new body based on the latest knowledge from aerodynamics research.

Enter the newly designed BMW 328 Coupes and the quest for the Mille Miglia.

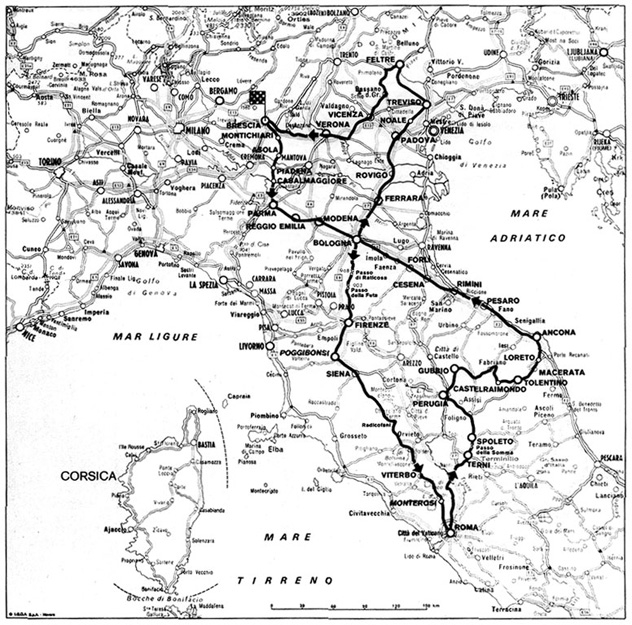

The Mille Miglia was the world’s longest road race at the time and led from Brescia via Cremona, Piacenza, Bologna, Florence and Siena all the way to Rome. The return leg of the race to Brescia took the drivers via Perugia, Ancona, Bologna, Ferrara and Venice. The drivers and their machines covered 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometres) – non-stop – through Italian countryside, towns and villages in what was from the outset one of the most exacting challenges available to man and machine. Success in the Mille Miglia was proof of a company’s competitiveness not only on the racing stage but also in automotive construction in general. A race course like that of the classic Mille Miglia would be thought of as pure insanity in today’s day and age, but throughout the 1930s the Mille Miglia was regarded as one of the best proving grounds for any production sports car.

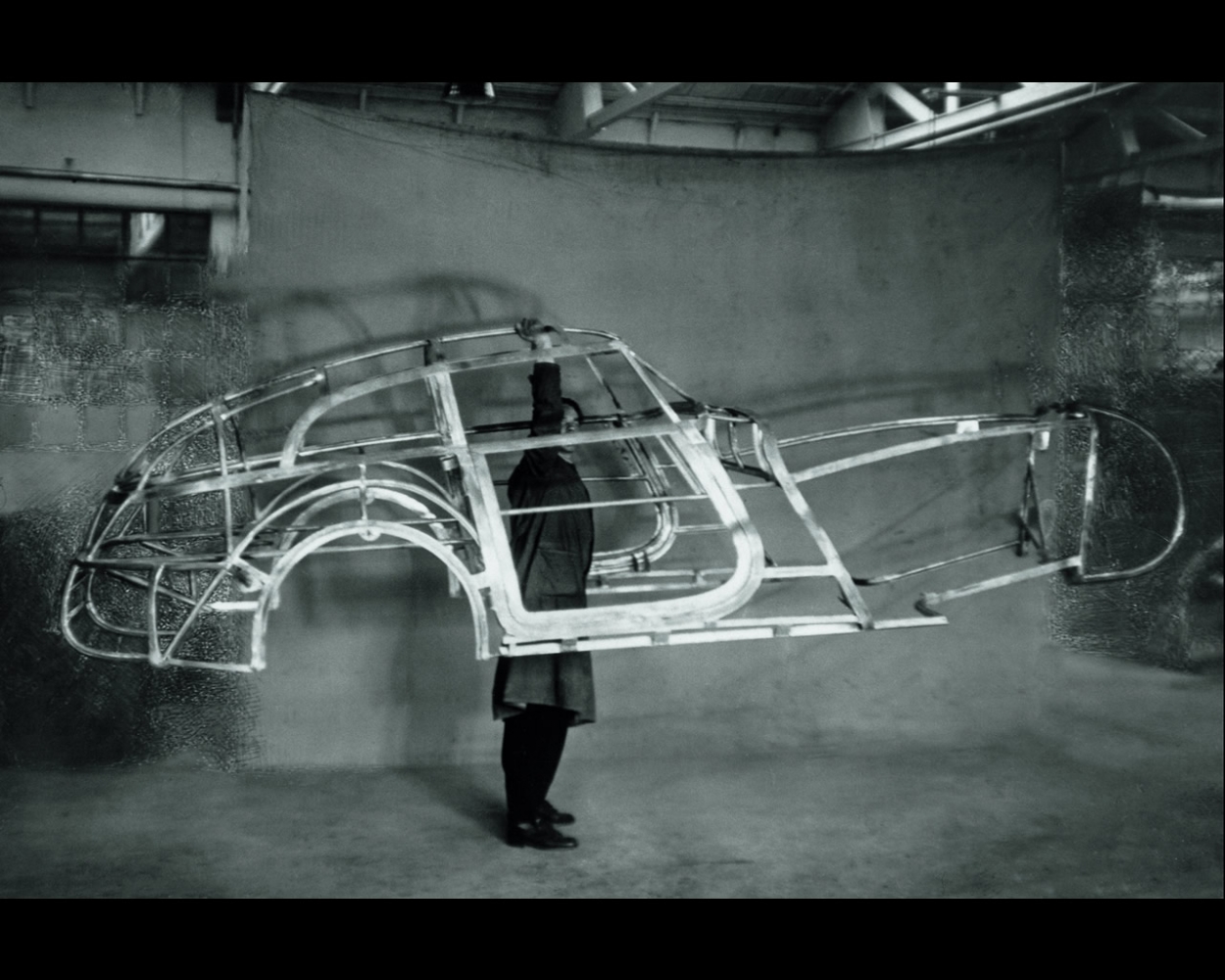

In 1938, clear evidence suggested that smaller-engined cars could achieve extremely high speeds through the use of lightweight, streamlined bodies. Open-top cars had been shown to be less aerodynamically efficient than hardtops, which they had been previously campaigning with the 328. In 1938 the decision was taken to build a hardtop racing saloon based on the BMW 328 Roadster. With the pressure building due to time restrictions, the racing department turned to Carrozzeria Touring to build a streamlined car for the start of the 1939 season. The Milanese coachbuilder had already completed a similar project for Alfa Romeo and agreed without hesitation. This highly advanced and extremely lightweight body consisted of a spaceframe tubed-chassis with an aluminum outer skin. The lightweight material helped to further reduce weight, while the production bulbous skin was streamlined for more aerodynamic efficiency rather than stunning looks.

The BMW 328-based Coupé lined up for the first time at Le Mans in 1939 with Prince Max zu Schaumburg-Lippe, the NSKK (National Socialist Motoring Corps) team’s leading driver, at the wheel. The “superleggera” Coupé – weighing just 780 kg – won the 2-litre class by an impressive margin, recording an average speed of over 130 km/h. That was enough to secure fifth place in the overall classification, fending off significantly more powerful cars in the process and raising hopes for the company’s chances in the Mille Miglia the following year (no Mille Miglia was run in 1939). The BMW cars were perfectly poised to emulate the achievements of the company’s motorcycles, which had already achieved impressive success in racing competition.

In 1940 this momentum gave rise to a car purpose-built for one reason only, to win the Mille Miglia. For the first time, a hardtop racing saloon produced in-house: the “Kamm Coupé” was built. A new streamlined body was duly created at the newly formed “Künstlerische Gestaltung” (Artistic Design) department, under the stewardship of Wilhelm Meyerhuber. The all-new space frame was made from the magnesium alloy Elektron and weighed just 66 lbs.

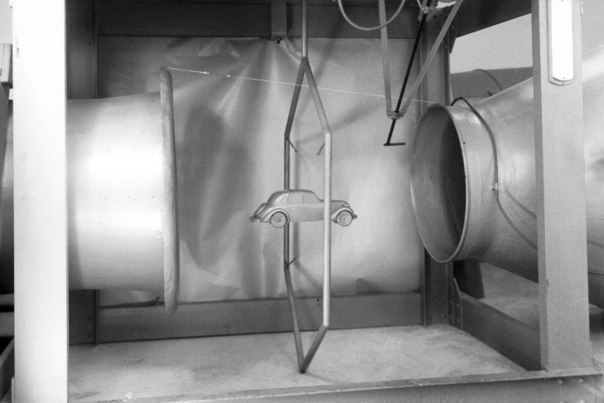

The outer skin was developed by the automotive engineer, Wunibald Kamm, who specialized in automotive aerodynamics and had been working on cutting edge research. His advanced research included a patent that specified that “The car body gradually tapers into a streamlined shape of sufficient leanness to permit the airflow to cling to the rear part of the body, but the streamline does not end in a point or an edge but the rear part of a streamlined car body is cut off and a flat rear face is formed.” The specifications tested by Professor Wunibald Kamm in the wind tunnel were followed precisely, and initial scale model wind-tunnel tests highlighted astonishing drag coefficient figures for the time. The average score for a vehicle in the 1930s was 0.55Cd, but Kamm’s test cars reduced that figure to a theoretical 0.24Cd. The aluminum body reduced weight and complimented the super low drag coefficient (For reference, the BMW Touring coupe was calculated to be approximately .35Cd).

The BMW 328 Coupes represent a seamless blend of function and aesthetic allure.

Again the experts managed to extract more power from the engine, the Roadsters now producing 95 kW (130 hp) from 1,971 cc and the Kamm racing saloon up to 100 kW (136 hp) – sensational figures for the time. The race engines used in the 1940 Mille Miglia were given reinforced crankshafts. These featured nine counterweights, including a reinforced central weight element which eliminated the risk of bending. These crankshafts and a number of other upgrades – notably to the valve control – enabled the race engines to run at speeds of up to 6,000 rpm. This pushed the engine output recorded on the test rig up to 136 hp. Production cars also benefitted from these advances. The experience with the race crankshafts was reflected in areas such as the development of the engine for the first post-war BMW, the “Typ 501”, whose crankshaft also had nine counterweights.

The “Kamm Coupé” was given its first opportunity to demonstrate its performance potential on the motorway between Munich and Salzburg. Setting a top speed of 230 km/h, it became the fastest BMW on record. However, the outbreak of war initially cast doubt on whether it would get the chance to show what it could do against its rivals.

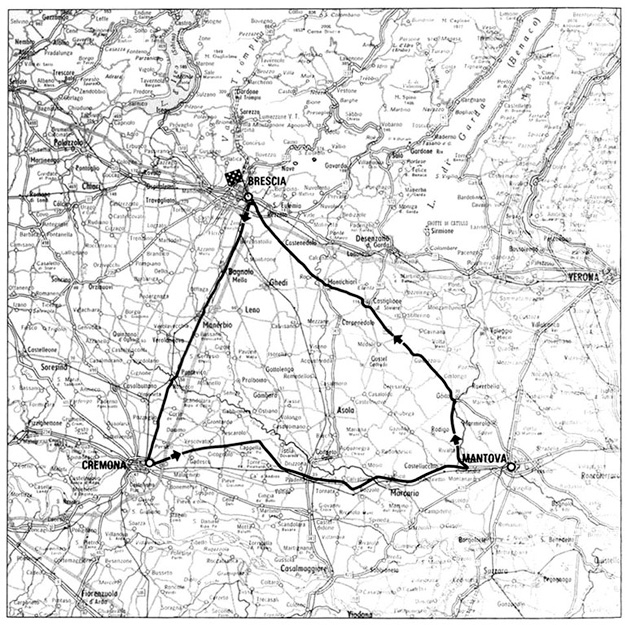

The political situation meant that only a handful of races took place in 1939 and 1940. One of those was the 1940 Mille Miglia. Although it still covered 1,000 miles, the drivers would not be competing on the classic route to Rome and back, but over a 167-kilometre triangular course, to be lapped nine times. The 1940 running of the Mille Miglia is still disputed by most sports racing aficionados to this day as to whether or not it should be classed as an official running of the race due to the dramatic reduction in the size of the course by the Mussolini regime. The new route followed well-surfaced roads through flat countryside and included a lot of long straight sections which were expected to lead to high average speeds. In a nod to tradition, the race was once again billed the 1st Gran Premio Brescia delle Mille Miglia.

For 1940, racers would still start from Brescia and race to Cremona, then Mantua, before returning to Brescia. This circuit would be lapped nine times, each lap a distance of roughly 62 miles. While traditionalists still cringe to mention this running of the iconic Italian race, it’s important to note that the Italian fans were overly enthralled with the new layout as they now were able to see the cars speed by nine times instead of only once.

The members of the NSKK team were entered to drive the three streamlined Roadsters, having represented Germany with great success in races abroad over the previous two years. Car number 71, the first streamlined Roadster, was piloted by Hans Wencher and Rudolf Scholz, the two other Roadsters – car numbers 72 and 74 – were crewed by Willi Briem/Uli Richter and Adolph Brudes/Ralph Roese respectively. The three teams were under instructions not to push too hard, but to maintain a good speed and look after their machinery. Although the aim was to finish as high up the standings as possible, the main priority was to complete the race and win the team prize.

The two Coupés, meanwhile, were entered by the ONS (the highest-ranking national sports authority in Germany at the time). Fritz Huschke von Hanstein and Walter Bäumer would drive the Touring Coupé, while two outstanding Italian drivers – Count Giovanni Lurani Cernuschi and Franco Cortese – had been recruited to pilot the works Kamm Coupé. While the target for these two Coupés was overall victory, tradition suggested that the Alfa Romeo team was a far more likely winner. BMW’s Italian driver pairing were certainly in with a chance, though, the Kamm Coupé having displayed superior handling in testing and reached much higher speeds than the Touring Coupé.

Waved by a green on his way at 6.40 a.m. on 28 April 1940, Touring Coupé driver Huschke v. Hanstein roared straight into the lead of the 2-litre category and never relinquished it over the full 1,503-kilometre race distance. After eight hours, 54 minutes and 46 seconds car number 70 duly took the checkered flag. Von Hanstein and his co-driver Bäumer had not only wrapped up the class honors – with an average speed of 166.723 km/h – they also took overall victory and, setting a mark of 174.102 km/h, recording the fastest lap average.

Top speed was measured at approximately 143mph!

The Italian crowd and much of the press was caught completely by surprise seeing the little German coupe fly across the finish line first, beating the Italian giants, many of which had power plants in the range of 3.0 liters. No other Mille Miglia winner before or since has matched the speeds achieved by the “Rennbaron” in his BMW 328 Mille Miglia Coupé with Touring body. The downcast Italians had to wait over a quarter of an hour for the second-placed Alfa Romeo of Farina/Mambelli. Third were Adolf Brudes and Ralph Roese in one of the three BMW streamlined roadsters. The other BMW starters filled fifth and sixth places. The Kamm Coupé was forced to retire with engine problems; up until its premature demise, however, it had been running close behind and may well have put up a strong fight for the win had it not succumbed due to engine lubrication issues.

The outstanding placings of the BMWs ensured that Munich also had the team prize to celebrate alongside victory in the overall classification. Its success in the Mille Miglia 1940 represented the crowning glory of the company’s already fruitful motor racing history to date. The 328 had proved that it was capable of sustaining incredibly high speeds over long distances without complaint. The car’s combination of impressive output and flawless road holding had shown that it was possible to overcome the challenge of far more powerful rivals. For BMW, this success represented an international breakthrough in European motorsport. The performance also underlined how far the development of aerodynamics and lightweight construction had progressed in 1940.

Exactly 70 years after winning the 1940 Mille Miglia – the BMW 328 Touring Coupé did it all over again. Again it was Giuliano Cané and Lucia Galliani who steered the Coupé majestically through the numerous stages and swept along the 1,000 miles through Italy without a single technical hitch. Enzo Ciravolo and Maria Leitner added the icing to the cake of BMW’s success by finishing third in a standard BMW 328 in another instance of Mille Miglia history repeating itself; 70 years ago BMW had also claimed third place. To be reminded of just how potent the 1940 cars still are today, you need only witness their journey to Italy for the event. There is not a transporter or trailer in sight; instead, just as they did 70 years ago, they travel from Munich to Brescia on their own power. And even more impressively, they complete the journey on a single tank of fuel; then, as now, the engines were not only powerful but also efficient. The drivers and cars can encounter a wide variety of weather conditions en route to Brescia and during the event itself, but nothing can dampen the spirits of the drivers and cars alike. Whether they’re basking in 27 degrees Celsius on the Adriatic or shivering just above freezing in the snow and mist of Monte Terminillo, the teams experience everything the Italian climate can throw at them. And today, just as they did back then, they power to victory in sumptuous style.

Due to the war, racing development was not able to continue. BMW’s next major 4 wheel motor racing venture came in the form of the BMW 700 where a new team of engineers was able to push the limits of a production vehicle after the chaos of WWII.

Latest posts by Tom Schultz test #2 (see all)

- 2025 Event Details - 13 May, 2025

- 2024 Durango Event - 24 February, 2024

- Drive 4 Corners 2022 Low-Key Event Concluded - 1 September, 2022